The Field Transcriptions: The Galerie Kahnweiler Stock Book (1907–late 1913) & Record of Shipments Abroad (1910–1920)

[English] This text is an analysis of the Field transcriptions of the Galerie Kahnweiler stock book (1907–late 1913) and record of shipments abroad (1910–1920). It constitutes an initial assessment of what new knowledge can be gained through their examination. Of the original two Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler’s notebooks which John H. Field transcribed in 1969 with the permission of the art dealer, the Galerie Kahnweiler stock book has been among the least accessible Kahnweiler documentation, and the record of shipments abroad has never been analyzed in detail. Today, the Field transcriptions throw into sharp relief the two main activities of Kahnweiler’s art business: the support of a core group of eight artists (Georges Braque, André Derain, Kees van Dongen, Juan Gris, Fernand Léger, Manolo, Pablo Picasso, and Maurice de Vlaminck), and the international dissemination of their art from 1910 to the onset of World War I. Furthermore, they illuminate the crucial moment of 1919–1920 when Kahnweiler reinstated himself as an art dealer. Without claiming comprehensiveness, the aim of the analysis is twofold: on the one hand, to bring to bear new insights on seemingly fixed ideas about Kahnweiler’s art business, and on the other, to model, by way of concrete examples, the potential for the practical application of this material in the context of art market, cultural transfer, and provenance studies.

How to cite this text :

Jozefacka, Anna and Luise Mahler, "The Field Transcriptions: The Galerie Kahnweiler Stock Book (1907-late 1913) & Record of Shipments Abroad (1910–1920)", Centre d'études Picasso, Musée national Picasso-Paris (September 2025). https://cep.museepicassoparis.fr/the-field-transcriptions/

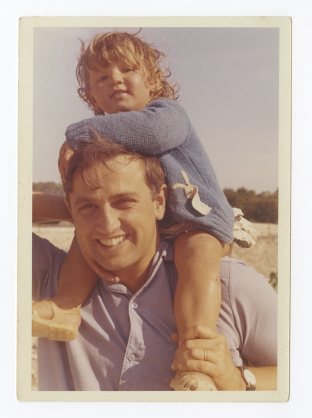

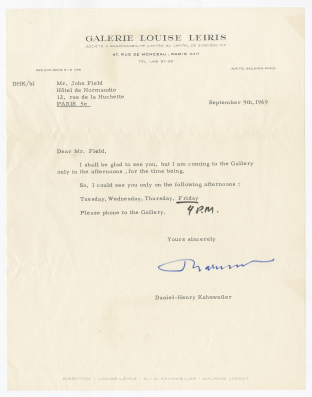

Gaps in the accounts of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler’s crucial first couple of decades in the art business have long vexed researchers and scholars alike. Until now, it has remained obscure how Kahnweiler achieved such a commanding position within modern art in as short a period of time—all despite his arrival to the Paris art market at the beginning of the twentieth century as a neophyte with a sole focus on emerging artists. Ambiguity regarding any gallery’s history often arises due to lack of access to complete gallery records, and Kahnweiler’s case is no different: without his documentation, for example, how can one identify from whom and how many artworks he bought? Which exhibitions precisely did he supply and with what, and was there a pattern to the circulation of his stock? How did he manage the day-to-day promotion of a strikingly diverse group of artists? And how did he reposition himself in the immediate aftermath of World War I, when almost his entire stock as of summer 1914 was under sequestration? No doubt he was the glue that held the Galerie Kahnweiler together, but without ready availability of gallery records to be subjected to rigorous investigation, none of these questions can be adequately addressed.[1] Kahnweiler understood the importance of access to his records and occasionally shared them with interested parties during his lifetime. In 1969, for example, he gave access and permission to transcribe two of these records, the stock book (1907–late 1913) and the record of shipments abroad (1910–1920), to John H. Field. (Figs. 1–2) The Field transcriptions are now part of the Musée national Picasso–Paris and accessible through its Centre d’Études Picasso.

The analysis that follows constitutes an initial assessment of what new knowledge can be gained through the transcriptions’ examination. Without claiming comprehensiveness, its aim is twofold: on the one hand, to bring to bear new insights on seemingly fixed ideas about Kahnweiler’s art business, and on the other, to model, by way of concrete examples, the potential for the practical application of this material in the context of art market, cultural transfer, and provenance studies.

Genesis of Kahnweiler’s Records

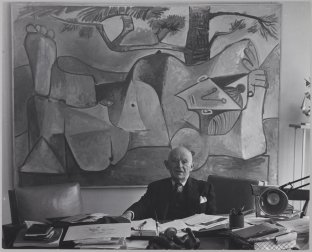

“I realized … I was not a creator but rather a go-between,” Kahnweiler declared in 1961.[2] (Fig. 3) In 1907, as Kahnweiler was first starting out, he took his lead from two of Paris’s foremost experts in contemporary art: the art dealers Paul Durand-Ruel and Ambroise Vollard. Unlike them, however, Kahnweiler consciously limited the activities at his Parisian gallery. In his showroom of merely sixteen square meters, no more than around two dozen artworks could be displayed at once. Over time, Kahnweiler’s operative principle instead became rapid distribution with the expressed goal to create a following for modern art.

Kahnweiler had instinct, and his management style panache. After an artwork arrived at the gallery at 28 rue Vignon, he would record it in a stock book and assign it a unique inventory number. Starting in the summer of 1910, he would also document artwork movement in a record of shipments abroad. Rather than large, pre-formatted ledger books, Kahnweiler chose to copy everything into small, portable, so-called “petits carnets noirs.”[3] These notebooks became central instruments in Kahnweiler’s mediation of some of the period’s most innovative artistic talent: unlike some European galleries, Kahnweiler did not employ an artistic director or curators at his establishment. Instead, he acted as a kind of one-person committee in dialogue with his artists.

Due to losses during World War I and curtailed access to the art dealer’s archives since his death in 1979, there is little material knowledge of Kahnweiler’s records. To date, what is known is based on partial accounts and some published examples indicating that the gallery’s records were extensive, and that they included the activities of the gallery’s imprint, the Éditions Henry Kahnweiler. That some of these records survived the war and the gallery’s sequestration is in part thanks to Kahnweiler himself, who, in keeping with his routine, had carried the notebooks with him during his annual summer leave starting in late July 1914. As such, his gallery’s most salient operational documents were with him in Italy when war broke out.

The stock book has been among the least accessible Kahnweiler documentation, and the record of shipments abroad has never been analyzed in detail. Today, the Field transcriptions of the two notebooks throw into sharp relief the two main activities of Kahnweiler’s art business: the support of a core group of eight artists, and the international dissemination of their art from 1910 to the onset of World War I. Furthermore, they illuminate the crucial moment of 1919–1920 when Kahnweiler reinstated himself as an art dealer.

Genesis of the Field Transcriptions

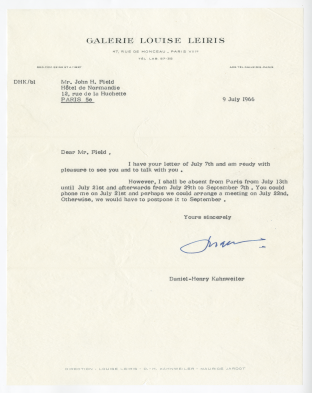

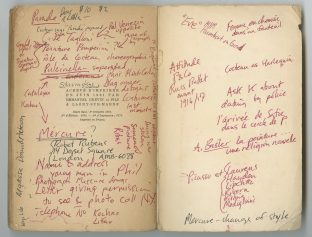

The Field transcriptions originated from in-person interactions between Field and Kahnweiler in the mid-to-late 1960s. (Fig. 4) Field first contacted the famed art dealer in summer 1966. Their conversation, held at Galerie Louise Leiris in Paris on July 22nd, allowed Field an opportunity to introduce himself and his doctoral thesis on Pablo Picasso, as well as ask questions.[4] He formulated them having read Kahnweiler’s 1961 interviews with Francis Crémieux: Field carried his heavily annotated copy with him on the occasion of their first meeting. (Fig. 5)

A native of Brooklyn, New York, Field received a master’s degree from the Courtauld Institute of Art in London in 1958. Five years later, he re-enrolled to pursue a doctorate under the supervision of Anthony Blunt and John Golding. Drawn to the coexistence of contrasting styles in Picasso’s practice since 1913, Field was stimulated by the recent scholarship on the artist coming out of the Courtauld. He envisioned his thesis as a sequel to Golding’s 1959 Cubism: A History and an Analysis 1901–1914, but modeled on Blunt and Phoebe Pool’s 1962 Picasso, The Formative Years; A Study of His Sources. In his dissertation, Field intended to analyze Picasso’s art and milieu from 1913 to 1925. Accordingly, his July 1966 conversation with Kahnweiler spanned several themes, from the interrelation between cubism and naturalism in the artist’s practice to Picasso’s interactions with art dealers, collectors, and the art market. In response to Field’s desire to meet the artist, Kahnweiler advised that now was not the time as Picasso was recuperating from surgery—but perhaps later.[5] Field never succeeded in fulfilling his aspiration.

It was not until 1969 that Field met with Kahnweiler for the second time. Now, he was concentrating his research on the spread of Picasso’s reputation and influence outside of France—he specifically zeroed in on the artist’s reception in Germany from before World War I until the 1920s.[6] Exhausting the period and secondary literature, including Kahnweiler’s own publications, Field concluded that only the art dealer could fill in the remaining gaps. In September of 1969, Kahnweiler once again received Field at his gallery.[7] He must have been sufficiently convinced by the emerging scholar’s informed inquiries to show him not only the documents directly pertinent to Field’s research on Kahnweiler’s activities from over half a century ago—the Galerie Kahnweiler stock book and the record of shipments abroad—but also permit him to transcribe them in full. (Fig. 6) But Kahnweiler might also have welcomed Field’s inquires for different reasons: at that time, Kahnweiler was engaged with Hommage à Kahnweiler, a highly personal exhibition that opened in February 1970 at Pfalzgalerie (now Museum Pfalzgalerie) in Kaiserslautern, Germany.[8] It is unknown how Field’s second visit with Kahnweiler relates to the accompanying catalogue’s inclusion of a list of exhibitions to which Kahnweiler contributed between 1910 and 1914.[9] Until now, this streamlined list—which provides information about types and numbers of works by Georges Braque, André Derain, Kees van Dongen, Juan Gris, Fernand Léger, Manolo, Picasso, and Maurice de Vlaminck, as well as the Éditions Henry Kahnweiler publications which Kahnweiler sent abroad—constituted the main record of the promotion of his artists outside of Paris.

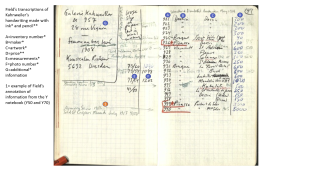

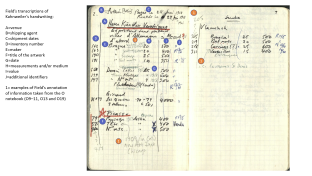

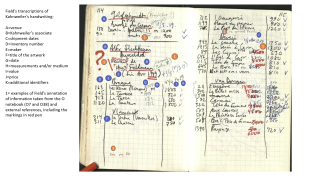

Field used two 17 by 10.5 cm notebooks with differently colored covers, orange and yellow, for his transcriptions—henceforth referred to as the O and Y notebooks. He transcribed the stock book in the O notebook, and in the Y notebook, the record of shipments abroad. Presumably, both notebooks originally had the same sheet count. However, at present, the O notebook has 94 and the Y notebook 76 sheets of paper. In both cases, Field glued some of the sheets together (O3, O19, Y13, Y37, Y93). It appears that he did so in instances where he turned over more than one page while copying the original documents, likely accidentally. The difference in the sheet count does not indicate any loss of actual sheets after Field had completed the transcriptions. Field also numbered the pages: in the case of the O notebook, he only numbered the right-hand side page, while for the Y notebook, he numbered each page with some exceptions, skipping page numbers 64-65 and 68-69 and repeating page 122. A comparison between the 1970 published list and the Y notebook indicates that little if any information was lost and thus skipping these pages was, once again, likely accidental.

Field further replicated Kahnweiler’s formatting by using black and blue felt pens to differentiate between alternative means of recording: black corresponds to Kahnweiler’s writing with presumably ink, and blue to his writing with pencil. As per Field’s annotations, in the original, the pencil at times gave the appearance of being erased (O1–2) and the writing transcribed with broken lines indicating erased but still visible information (for example, O13). However, copying errors on Field’s part should always be considered a possibility. Indeed, Field recalled asking Kahnweiler to assist him in deciphering some of the art dealer’s handwriting.[10] This is probably most significant for numbers rather than letters, specifically similarly looking ones like 1 and 7 (the latter written without a horizontal crossline) as well as 4 and 9. See, for example, the eighth line from the top on page Y33, where the last digit can be verified as “367” thanks to comparison with the transcription of the stock book on page O19. Field’s handwriting can be difficult to decipher at times as well.

Both notebooks also contain Field’s numerous annotations, generally distinguished from the original transcriptions through his use of different colors—light blue-green, blue, red, and others. Beyond regularly correcting and clarifying his original transcriptions and inserting background information, Field’s annotations relate to a research campaign in the late 1980s, during which Field analyzed the transcriptions with the goal of identifying Kahnweiler’s Picasso stock and establishing its acquisition history.[11] A possible impetus was the publication of Pierre Assouline’s biography of the art dealer, in which the information about the existence of his notebooks was first made public.[12] As for Field’s focus, he aimed to compensate for the fact that Kahnweiler maintained the stock book with only rare instances of recorded dates. Within the Galerie Kahnweiler records, dates for paintings, papiers collés, and sculptures were listed in the photo albums (these albums did not document drawings and prints).[13] Field, however, was not privy to Kahnweiler’s photo albums during his visits. Instead, he used his transcription of the record of shipments abroad, the catalogues raisonnés Pierre Daix had compiled of Picasso’s Blue and Rose years (in 1966 with Georges Boudaille) and cubist period (in 1979 with Joan Rosselet), as well as a selection of other primary and secondary sources to establish the timeline of Picasso entries in the stock book. These materials provided Field with the earliest and latest possible dates for Kahnweiler’s inventory of the artist’s artwork, as well as some information about the dealer’s sources. Field worked under the assumption that Kahnweiler inventoried the artwork in order of acquisition and soon after they arrived in the gallery.

To pithily size up Kahnweiler’s concentration on like-minded art dealers and artists’ associations in Germany and Eastern Europe in his promotion of Picasso prior to World War I, Field eventually borrowed the Cold War-era term Ostpolitik, which stood for the easing of tensions between East and West Germany in the late 1960s. His application of the term entered Picasso literature in the mid-1990s through John Richardson. The two first met in New York City in the summer of 1965 in the context of Field’s dissertation research. In 1991, after reading the newly published first volume of Richardson’s Picasso biography and breaking an interim of noncommunication, Field offered him access to his on-and-off research on Picasso since the mid-1960s for Richardson’s sequel.[14] For Field, the offer was a gesture intended to reciprocate Richardson’s helpful advice given back in 1965, and for Richardson, a hard-to-pass opportunity. Subsequently, Field assisted the biographer with research for his 1994 essay “Picasso und Deutschland vor 1914” in addition to the second volume of his Picasso magnum opus which appeared two years later.[15] Richardson recognized the role Field’s research played in their realization, crediting him for it as well as the term Ostpolitik in connection with Kahnweiler.[16] Field in part relied on his transcriptions of Kahnweiler’s stock book and record of shipments abroad to supply Richardson with such depth of information that the biographer had to resort to relegating many details to his notes.

The Orange Notebook: The Stock Book

The Field transcription of the stock book represents a complete record of what Kahnweiler amassed as his gallery’s inventory—1800 works in total—from spring 1907 to the end of 1913. As such, it offers new information with which to evaluate the existing understanding of the Galerie Kahnweiler’s vast contents, and for the first time ever, to consider individual Kahnweiler artists’ production against the context of his entire stock.

As the Field transcription of the stock book shows, Kahnweiler recorded information on both the left- and right-hand side pages, with the bulk of the information relegated to the latter. There, from left to right, the dealer inserted the inventory number, maker, title or description, and finally the price for each artwork. Kahnweiler assigned inventory numbers in consecutive order regardless of the artist, beginning with inventory number “1,” a watercolor by van Dongen (O1), and ending with inventory number “1800,” a painting by Léger (O90). The dealer identified paintings and sculptures by short titles, but works on paper primarily by their medium and, infrequently, their date. As already mentioned, Field annotated that Kahnweiler entered the prices in pencil, suggesting that he considered them subject to change. On the left-hand side pages, Kahnweiler also irregularly recorded measurements and photo numbers along the right margin. (Fig. 7) Since Kahnweiler started photographing his inventory only in 1910, he inscribed these details from that year onward on an as needed basis. Unlike the running stock list, Kahnweiler created separate photo number sequences for each artist whose work he photographed. The stock book confirms the following sequences: Picasso 1-1000; Braque 1001-2000, Derain 2001-3000, Vlaminck 3001-4000; Gris 5001-6000; and Léger 6001-7000.[17]

Field’s annotations throughout the O notebook point to the shortcomings of the stock book as the sole source of information for identifying individual artworks, underscoring the utility of cross-referencing the stock book with the record of shipments abroad. As discussed in the previous section, cross-checking inventory numbers between the stock book and the record of shipments abroad can lead to the identification and correction of recording errors, as well as help date individual entries in the stock book (as Field’s annotations point out). Consulting either or both transcriptions jointly can also lead to the identification of inventory numbers that are only partially known. One such case is a painting by Braque titled Still Life: “2e étude” and hitherto dated 1914 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection), with its previously partially identified inventory number of “93[?]4.” Based on the known information, there are only two possible matches in the stock book for a work by Braque in the 900 sequence: the inventory numbers “934,” titled “Mandoline Verre et B[outeille]” (O47), and “984,” titled “La Table de Bar” (O50). Additional information listed in the stock book for the inventory number “934,” the photo number “1202” and the measurements “73/54” (O47bis), match known information for Still Life: “2e étude” and confirm a positive match. This identification, in turn, provides the historic title and points to an earlier date for the work. The stock book sequence 931–8 reveals that the painting was among a group of eight Braques, which Kahnweiler inventoried in 1912 thus dating Still Life: “2e étude” to no later than that year. Among the remaining seven works six have been identified and are dated in the literature as from the period 1911–12, including Violin: “Mozart Kubelick” (1912; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection), a painting Kahnweiler logged as number “935” and then quickly shipped to a September 1912 exhibition in London (Y38).[18] Stylistic deviations of Still Life: “2e étude” from Braque’s other works of 1912 suggest repainting and probably formed the basis for the historical dating that has been handed down in literature since 1925.[19] Finally, Kahnweiler tended to document an additional degree of details about artworks in the record of shipments abroad—for example, the Braque painting inventoried in the stock book under the number “751” and the abbreviated title “Les Poissons” (O38) is listed twice in the record of shipments abroad, appearing with a more elaborate title and measurements as “La Pannier de Poissons [sic]” and “Pannier de Poissons [sic]” with number 12 French standard canvas size (Y25 and Y100). With this information in hand, it is possible to suggest that the painting likely corresponds to Basket of Fish (ca. 1910; Philadelphia Museum of Art).[20]

The processes of buying and inventorying should not be equated when consulting the stock book—a potential delay in carrying out the latter must be considered. Nevertheless, the two often went hand in hand; as a result, the inventory sequence represents a chronology of Kahnweiler’s acquisitions in a broader sense. With that said, further complexity arises with the addition of older artwork among the majority of more recent output. Because Kahnweiler rarely listed dates and did not record provenance-related information in his stock book at all, such occurrences are not readily identifiable, and it should not be assumed that the source of purchases were exclusively the makers themselves. Kahnweiler also acquired their works from other sources, including artists. An example for the latter is the Picasso inventoried as “114,” which Kahnweiler purchased from Vlaminck (O6).[21]

The beginning of the stock book records Galerie Kahnweiler’s rapid transformation from a tenuous business plan to a steadfast enterprise specializing in a select group of emerging artists. It also points to the gallery’s possibly multifarious origins. In his unpublished analysis, Field speculated that the early entries of prints by Edouard Vuillard and August Rodin, inventory numbers “3” and “4” respectively (O1), were works Kahnweiler bought for himself prior to deciding to open a gallery. It is indeed conceivable that the novice dealer culled his private holdings to quickly build up his gallery’s stock; however, whatever the source of their artworks, long-established artists are an anomaly not just at the start of the stock book but throughout. This affirms that while operating Galerie Kahnweiler, the dealer did not engage with the secondary market in any substantial way, instead directing his efforts and resources at emerging artists. Those artists who became synonymous with Kahnweiler quickly emerged from a diverse group of starter acquisitions. Among those already identified as the dealer’s initial purchases at the Salon des Indépendants of 1907 are Charles Camoin, Derain, Van Dongen, Othon Friesz, Henri Matisse, Paul Signac, and Vlaminck.[22] In addition, Kahnweiler listed Edvard Diriks, whose salon entry Seine-et-Marne (printemps) is a possible match for inventory number “18” with the title “Seine” (O1); Charles Guérin, who exhibited a work titled Paysage, a possible match for inventory number “20” titled “Paysage” (O1); and Francis Jourdain, who exhibited La Fête sous les arbres, a possible match for inventory number “28” titled “La fête” (O2).[23] Most of these artists are represented by only a handful of works in the stock book. This includes Camoin and Pierre Paul Girieud, two artists who held exhibitions at the gallery in 1908.[24] Francisco Durio (Paco Durio), who jointly exhibited with Girieud, is excluded from the inventory all together (however, he is listed once in the record of shipments abroad; Y90). With regards to the more substantial inventory totals among these Kahnweiler outliers, the standouts are Friesz and Jan Verhoeven with sixteen and eleven works respectively. Most of the artists just named were tied to fauvism; however, ascribing the heavy presence of artists associated with fauvist circles in the first part of the stock book to Kahnweiler’s initial one-sided interest would be false. The inclusion of Picasso amongst his early acquisitions, comprised of three works on paper inventoried as numbers “77–9” (O4), highlight how independently-minded and instinctive Kahnweiler was from the start.

While the information contained in the stock book does not add to the present understanding of how Kahnweiler established important connections with his artists, the early sequence of the stock book does nevertheless confirm Kahnweiler’s open-ended yet brief search for the emerging artists with whom he quickly established exclusive long-term partnerships. One by one, the dealer entered works by artists he had just met—Van Dongen, Derain, Vlaminck, Picasso, and Braque, inventoried in that order—with increased frequency and volume, while at the same time the number of works by others petered out slowly (O1–5). From the beginning of 1909 forward, the stock book is decisively dominated by those five artists. However, in 1911, the stock book registers a change. That year, Kahnweiler stopped inventorying works by Van Dongen, and in early 1912, commenced adding works by a new artist, Manolo (Manuel Martinez Hugué). Although most strongly associated with cubism since Braque’s exhibition at the gallery in November of 1908, Kahnweiler, as he always did, felt free to expand his offerings in yet another direction. He first logged twenty-nine sculptures and works on paper by Manolo, whose style is not easily classified, as inventory numbers “817–45” (O41–3). At the start of 1913, Kahnweiler then took on Juan Gris, whose work is first recorded with the inventory number “1202” titled “guitare espagnole” (O61).[25] He also signed Fernand Léger, whose studio contents the dealer purchased in one transaction.[26] With their respective new takes on cubism, both artists represented Kahnweiler’s willingness to expand stylistically. Unlike the ready commitments made to the five artists he just met in 1907, in the case of Manolo, Gris, and Léger, the dealer waited to get to know them before offering them his exclusive representation. Only from that point on did he inventory their works. Kahnweiler knew Gris since probably 1908, but inventoried his first painting after February 20, 1913, the date of their written contract. The stock book suggests a similar scenario for Léger, whom the dealer knew since 1911. According to the stock book, Kahnweiler inventoried a long sequence of 192 Légers, inventory numbers “1494–1686” (O75–85), on the date they signed their contract (October 20, 1913) or soon after. The sequence starts with Nudes in the Forest (1909–11; Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo), the artist’s sensational entry to the 1911 Salon des Indépendants, which drew notice from Picasso and led Kahnweiler to Léger’s studio.

Each artists’ inventory totals up to the end of 1913 capture the depth of Kahnweiler’s commitment to his stable: Picasso with 422 works, Vlaminck with 329, Derain with 276, Braque with 216, Léger with 193, Van Dongen with 140, Manolo with 94, and Gris with 47. The differences should be attributed to the individual artist’s rate of production, and in the case of Manolo and Gris, with the later beginnings of their artistic careers, rather than any partiality on Kahnweiler’s part. With that said, there is one exception. As mentioned above, of the eight artists, Van Dongen is the only one whose work Kahnweiler discontinued buying. However, as the stock book makes clear, the dealer did not stop acquiring when Van Dongen signed a contract with Galerie Bernheim-Jeune at the end of 1908, but when Kahnweiler ceased to be convinced by Van Dongen’s artistic direction.[27] The artist’s last work is the inventory number “691,” titled “La loge ‘Madrid’” (O35) and logged before May 15, 1911, the date when Kahnweiler dispatched the painting to Cologne (Y15). But even this does not adequately reflect Kahnweiler’s relationship with Van Dongen, as is explained in the next section focused on the record of shipments abroad.

Examining how Kahnweiler inventoried artworks can lead to new insights into the intricacies of his business practices. The examples selected here focus on earlier artworks by the Kahnweiler artists, which the dealer acquired while mainly engaging with their most recent production. Just a few inventory numbers down from Braque’s above mentioned Still Life: “2e étude” and Violin: “Mozart Kubelick” the dealer recorded two paintings by Picasso which the Spaniard painted nearly a decade prior. Their titles identify them as related to one another: the inventory number “939” is listed as “Portrait de Soler” or Portrait of Soler (1903; The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg) and the inventory number “940” as “[Portrait de] Mme Soler” or Madame Soler (1903; Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich) (O47). The sitters were the tailor Benet Soler Vidal and his wife Montserrat, supporters of Picasso during his Barcelona years. In 1903, in addition to these two portraits, Picasso also executed a large group portrait of the entire family, The Soler Family (1903/1912–13; Musée des Beaux Arts, Liège). In 1912, Kahnweiler acquired all three paintings directly from Señor Soler.[28] However, he did not inventory them as one group: the family portrait entered the stock book separately as number “1170” (O59). The separation of the three paintings, acquired at the same time from the same source, arose from Picasso’s insistence on repainting his large earlier canvas, thus causing Kahnweiler to wait to inventory it. Braque’s 1912 still life and Picasso’s 1903 portrait of Señora Soler share not only proximity in Kahnweiler’s stock book, but early exhibition history as part of the Galerie Kahnweiler stock, notably his first shipment to the United States in 1913 (Y50–1).

If Still Life: “2e étude” and Violin: “Mozart Kubelick” entered the stock straight from Braque’s studio and soon after he had finished them, his painting Carrières Saint-Denis Church (1909; Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris) had a completely different journey into Kahnweiler’s stock book. As will be fully fleshed out in the next section, Kahnweiler hastily purchased this 1909 painting from Braque in September of 1912 and inventoried it as number “1044” (O53) sometime in November of the same year.

The final example is the record of four Picasso paintings with the inventory numbers “1490–3” (O75), which document Kahnweiler’s transaction with Gertrude Stein as noted by Field in his annotation (O75bis). According to a letter from Kahnweiler to Stein dated October 17, 1913, the dealer acquired from the writer “Le jeune fille sur la boule” or Young Acrobat on a Ball (1905; Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow); “La grande composition rouge” or Three Women (1908; The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg); and “La femme avec le linge” Nude with a Towel (1907; private collection; Z II, pt. 1: 48) in exchange for 20,000 French francs and a recent painting by the artist, “L’homme en habit noir” or Man with a Guitar (1913; private collection; Z II, pt. 2: 436).[29] As has already been established through the examination of the Galerie Kahnweiler labels adhered to the backs of these artworks, Kahnweiler inventoried the three Stein paintings together, inventory numbers “1490–2.” What the Field transcription of the stock book adds to the current knowledge of the transaction is the inventory number of the painting selected by Stein, as well as the insight that Kahnweiler inventoried it as the fourth work in his stock book sequence, inventory number “1493” titled “L’homme en habit noir.” It can thus be concluded that Kahnweiler inventoried the paintings once he had reached the agreement with Stein and after she made her selection of a recent painting, but before his payment on January 15, 1914.[30]

As previously stated, the inventory number “1800” (O90) is the last entry in the stock book Field transcribed with Kahnweiler’s permission in 1969. Field’s cross-referencing of the stock book with the record of shipments abroad allowed him to date the end of the former to the close of 1913 and beginning of 1914. The descriptive title Field devised for his transcription—“Transcript/Kahnweiler’s Notebook No. 1/Numbered Stock List 1907–1914/& some postwar”—reflects that he also partially reconstructed the sequence of later inventory numbers (O, unnumbered pages) based on the information in the record of shipments abroad, which dated up to 1920. Given the fact that Kahnweiler documented inventory numbers as high as “1993” for a Vlaminck (Y122bis)—and even higher ones are accounted for in the literature—it was logical for Field to conclude that Kahnweiler continued with his inventory using the same sequence. Although its existence has not been verified, it is reasonable to think that Kahnweiler started a second stock book in step with the new calendar year, that is, January 1914.[31] With inventory numbers as high as “2246” accounted for Braque, for example, Galerie Kahnweiler had an influx of over 400 artworks during the first half of 1914, a significantly higher intake than the average during the previous seven years.[32]

The Yellow Notebook: The Record of Shipments Abroad

In total, Kahnweiler organized only four special exhibitions at his gallery, all in 1908, for reasons which remain hypothetical: demand for the new art which he championed had primarily emerged outside of Paris, and in reality, the gallery’s premises also likely proved too small to organize larger events. According to his biographer, Kahnweiler believed that “Paintings are made to circulate, to be disseminated, to be exchanged. But they cannot be artificially pushed.”[33] So, as the number of inquiries from outside organizers increased between late 1909 and early 1910, he opted to expand his presence on the international art market. He started with his native region, the prevailing language (German) of which he spoke. Among the first, if not the first, to contact him were the Spolek výtvarných umělců Mánes (Mánes Association of Artists) in Prague and the Sonderbund Westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler (Special League of West-German Art Lovers and Artists) in Düsseldorf.[34] Kahnweiler’s first sizable shipment of stock, however, was to the Neue Künstlervereinigung (New Artists' Association) in Munich for their second exhibition at the Moderne Galerie (Heinrich Thannhauser).[35] Enlisting the services of local shipping agent Maurice Pottier, Kahnweiler sent three works on paper by Picasso and numerous paintings by Braque, Derain, Girieud, and Vlaminck to Germany on June 28, 1910 (Y2–3). From then on, he concentrated the strategic marketing of his artists in the cultural hubs of Central and Eastern Europe.[36] Between 1910 and 1914, Kahnweiler circulated his stock in Basel, Berlin, Breslau (present-day Wrocław), Budapest, Cologne, Dresden, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Munich, Prague, Vienna and Zurich. At the same time, he supplied fellow art dealers, private clients, artists’ associations, museums, and special exhibition organizers in Amsterdam, Chicago, Edinburgh, London, Moscow, New York, Rome, Saint Petersburg, and Stockholm, and, surprisingly, Lyon. The first group of documented photographs that he sent out—six unidentified Picassos—went to August Liebmann Mayer, the Munich-based historian and curator of Spanish art and Jusepe [José] de Ribera in particular (Y14). By May 1914, the date of his last shipment prior to the war, Kahnweiler had completed over 90 dispatches. Over time, Kahnweiler’s professional relationships positioned him to assist with critical publications—and, most importantly, to help organize solo exhibitions for all of his artists with the exception of Gris and Léger.

Judging by the Field transcription, Kahnweiler used the left- and right-hand side pages to document a continuous list of dispatches in his record of shipments abroad, which he referred to as his “Tableaux & envoyés au dehors” (henceforth “the record”). In pursuit of lean business procedures tuned on efficiency, Kahnweiler initially tried to track his shipments’ circulations in his agenda, but this practice must have proved unproductive because he switched formats on October 5, 1910 (front endpaper and Y1). Aside from the first one, the art dealer began each shipment entry with a header, stating the name and location of the recipient as well as often listing the shipping agent’s name, the dates by when and to whom the artwork had been promised, sent, and returned, and the surcharge in percent. This information was followed by a list of content for each shipment arranged by artist, but not necessarily in any particular order, and formatted according to a formula that, in turn, adhered generally to chronological order. This format comprised information listed in uniform sequence: an artwork’s inventory number; maker; title (not always but on average more elaborate than in the stock book); date (only from shipments made in spring 1912 forward and selectively at that; Y34); dimensions in the standard French canvas format (in the case of paintings), medium (in the case of works on paper and sculptures), edition numbers (in the case of prints and books) or photo numbers (in the case of photographic reproductions); value and, if applicable, price (in either French francs and/or the venue’s local currency such as “Mark”); and lastly, if applicable, the next venue. (Fig. 8) Some of the entries include additional identifiers, among which are single letters inscribed next to the value or sales price of the artwork: V, R, D, E, A, L are the most frequent. For example, the letter “D” likely stands for “déposé” or deposited, while “V” stands for “vendu” or sold, indicating the sale of an artwork, and “R” for “rentrés” or returned. Moreover, the last portion of Field’s transcription covers Kahnweiler’s activities during the immediate aftermath of World War I (Y114–35). While following the same formatting in principle, the information conveyed in these pages also differs in important details. As established further below, the formatting adjustments reflect Kahnweiler’s ways of adapting to postwar conditions as a foreigner and former enemy alien.

Extensive details listed in the record can assist in closing significant informational gaps. By way of example, in the context of the aforementioned Neue Künstlervereinigung exhibition in Munich, the record specifies that Kahnweiler valued a Picasso work on paper with the inventory number “375” and title “Tête” at 400 French francs (Y2), and that he sold it during the showing. Thanks to a reproduction of the work included in the exhibition catalogue, the work in question, Head of a Woman (1909; The Art Institute of Chicago), has long been identified as on display in Munich in 1910. What the record adds to the drawing’s to-date provenance is its inclusion in Kahnweiler’s inventory, its monetary worth at the time of the exhibition, and its sale during its run.

Moreover, the inventory number, the primary identifier between the stock book and the record, tracks an artwork across multiple exhibitions as well as whether it found a buyer. Such is the case with Picasso’s already mentioned Madame Soler, inventory number “940,” which Kahnweiler sent to Munich in 1913 after touring it in New York, Chicago, and Boston as part of the International Exhibition of Modern Art or Armory Show (Y50 and Y70). (Fig. 9) When working with his transcriptions, Field realized the magnitude of insights such as this one—he shared them with Richardson during their collaboration, who, in turn, published the information on Kahnweiler’s sale of Madame Soler for 3,500 French francs to or via Georg Caspari’s newly opened Munich gallery (Y70).[37]

The Field transcription also allows to assess inaccuracies and omissions in the 1970 published list of Kahnweiler’s contributions to exhibitions between 1910 and 1914.[38] Of the over 90 shipments listed in the record, only 61 were included in the published list. One example of misguided information published concerns the earliest contributions Kahnweiler made to the aforementioned exhibitions in Prague and Düsseldorf—both are entirely omitted from the list. Another is the inclusion of Girieud and only three, rather than four, of the dealer’s paintings by Derain in the 1910 Neue Künstlervereinigung exhibition. Finally, there is the example of a shipment of forty-six photographic reproductions to Otto Feldmann in Berlin in November 1913, also omitted from the list. Field’s transcription provides individual photo numbers (Y77): one of the earliest among them was the 1904 Portrait of Mademoiselle Suzanne Bloch (Museu de Arte, São Paulo), corresponding to inventory number “638” (O32). Knowledge about each photograph not only helps explain how these pictures extended the temporal span of the actual physical artwork, limited in the Berlin exhibition to Picasso’s cubist output between 1907 and 1913, but also how they may have provided the local public with an experience similar to that of Kahnweiler’s clients viewing the photo albums in Paris.

Based on the information about the more than 90 shipments documented in the record, a few examples stand out. They do so because they either shed light on little-understood projects or refute the common assumption that the dealer marketed his artists’ work exclusively outside France. Moreover, the variety of exhibitions in which Kahnweiler partook shows that he invested in all of his artists, and that he extended this policy to Gris, Léger, and Manolo as soon as he began to represent them. At the same time, it becomes clear that Kahnweiler’s promotion of Gris and Léger could not flourish to the same extent because of the outbreak of World War I.

Like other dealers, Kahnweiler assumed the position of his artists’ representative, but, more so than many of them, he also acted as their curator and guardian. He did so by carefully overseeing all inquiries with an eye toward educating the larger public about modern art as well as guaranteeing artistic integrity. For the most part, this trusting arrangement worked seamlessly and ensured the artists peace of mind, but, naturally, Kahnweiler and his artists did not always see eye to eye—especially in moments of artistic breakthroughs such as in the summer and fall of 1912 in the cases of Braque and Picasso. Picasso, for example, expressed dismay over the choice of work reproduced in the Sonderbund’s exhibition catalogue that year. In a letter to the dealer dated July 15, he wondered why Kahnweiler had given his permission to illustrate The Actor (1904–5; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) “instead of another better and more recent one” (Y33).[39] A couple of months later, Braque quarreled with Kahnweiler over the inclusion of one painting in an exhibition organized by the Moderne Kunstkring (Modern Art Circle) in Amsterdam, the artist’s landscape Carrières Saint-Denis Church (1909; Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris) (Y40–41). A September 16 letter from the artist makes plain that it was Braque himself who had dispatched it to Holland before leaving for Sorgues that summer.[40] Back in 1909, Kahnweiler had passed on buying Carrières Saint-Denis Church out of the artist’s studio, but now Braque had forced his hand: Kahnweiler needed to acquire the painting to uphold his monopoly on the artist’s production. The dealer purchased the landscape while it was already in Amsterdam, retrospectively adding it to the record and the stock book as inventory number “1044” when it returned to Paris in November 1912 (O53 and Y41).

Braque’s September 16 letter also reveals that Kahnweiler had little intention of participating in the exhibition in Amsterdam in the first place. One probable cause for his reluctance may have been that, although Braque and Picasso were to be given pride of place in the installation, the organizers framed Henri Le Fauconnier as cubism’s leader, and had also asked the so-called salon or formulaic cubists Roger de la Fresnaye, Albert Gleizes, and Jean Metzinger among others to contribute.[41] Indeed, Picasso too had acted on his own and asked the dealer to submit at least one painting he still owned, titled “L’Homme à la pipe” and dated 1912 in the record (Y41), to the exhibition. But unlike in Braque’s case, Kahnweiler did not insist on purchasing Man with a Pipe (1911; Kimbell Art Foundation, Fort Worth, Texas) retrospectively.[42] Seeing his artists being adamant about their participation, Kahnweiler relented and prepared a shipment that included Derains and Vlamincks in addition to Braques and Picassos from his stock (Y40–41). But this was not enough to settle the score with Braque: in additional letters from Sorgues, the artist reasoned, “You do not really compensate for your demands,” and then doubled-down: “I hope they [the exhibition organizers] will be satisfied with what you gave them. Nonetheless, we will have to talk about all this in Paris.”[43] Their disagreement over what their verbal agreement exactly entailed precipitated a change in how Kahnweiler dealt with his artists. On November 30, shortly after Braque’s return to the capital, he and Kahnweiler signed an exclusive contract spelling the terms of their agreement out in writing. It was the first of Kahnweiler’s prewar artist contracts, with others shortly following suite.

Another example for an exhibition that stands out among the over 90 shipments concerns the 1914 solo showing of Braque’s work in Dresden, for which, to date, no catalogue or references in the period literature have been found. The first mention of this monographic presentation dates to 1932.[44] According to George Isarlov, it was to be staged at the galleries of Emil Richter in Dresden and Otto Feldmann in Berlin and comprise thirty-six paintings and two works on paper. The 1970 published list accounts for the exhibition, but specifies only the Emil Richter venue and its contents as twenty-nine paintings and nine drawings.[45] Kahnweiler’s record, on the other hand, indicates that he shipped twenty-nine paintings and two drawings to Richter from Paris on February 10, and an additional four paintings and three works on paper from the art dealer’s stock arrived in Dresden via Essen (Y95–7).

The list of works in the record makes clear that the selection provided a far-reaching survey of Braque’s practice, ranging from the 1905–1906 fauve landscape Anvers: Les Bateaux pavoisés (Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation, on deposit at the Kunstmuseum Basel), inventory number “730” (O37), to the 1913 cubist Woman with a Guitar (Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris), inventory number “1466” (O74). But did the exhibition ever become properly installed and publicly viewed in Dresden, and did it travel on to Berlin as Isarlov stated? Although the exhibition can be understood more comprehensively thanks to the record, these questions remain unanswered.[46] All works except for Anvers: Les Bateaux pavoisés, which was marked as sold, eventually returned to Paris on June 9, 1914. Their return is confirmed by the fact that paintings dispatched to Dresden, such as The Port at La Ciotat (1907; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), Still Life with Metronome (1909; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection), and Violin and Sheet Music: “Petit Oiseau” (1913; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection), documented as inventory numbers “720,” “467,” and “1348” respectively, were sequestered from Kahnweiler’s gallery in December that year (Y85 and Y87).

The next example contains two known instances which are worthy of consideration because they contradict the current understanding of Kahnweiler’s exhibition policy. In early 1913, Kahnweiler submitted three paintings by Vlaminck to the Salon des Indépendants, despite his principle of relieving his artists from the need to show at the annual event (Y60). Or, this principle did not apply to all of his artists equally. The fact remains that Vlaminck was not yet under written contract with the art dealer until a couple of months after the salon had closed on May 18, and that Kahnweiler was not listed as the artist’s representative in the accompanying catalogue, a right he had made use of at the very start of his art business.[47] In light of the example of Braque’s and Picasso’s independent loans to the 1912 Moderne Kunstkring exhibition, Vlaminck’s participation in the salon may have been another instance of Kahnweiler needing to find a better solution after reaching an impasse with an artist wishing to exhibit his work, in this case locally. During the following year, in March of 1914, Kahnweiler made another peculiar choice involving Vlaminck: he submitted artwork to the Exposition Internationale Urbaine de Lyon, a world’s fair with two sections devoted to the arts (Y104).[48] Rather than sending a full selection of his artists, Kahnweiler opted to exclude Braque, Gris, Léger, Manolo, and Picasso (Van Dongen submitted two paintings independently citing Galerie Bernheim-Jeune). He sent five paintings by Derain and Vlaminck: two recent landscapes by Vlaminck, inventory numbers “1819” and “1859,” and three still lifes (two of which were by Derain), inventory numbers “847,” “989,” and “1140” respectively, and which were labeled “Paris, Galerie Kahnweiler, 28, Rue Vignon” in the accompanying exhibition catalogue.[49] As in the case of the Picasso photographs dispatched to Feldmann in late 1913 as discussed above, references to either exhibition were left off the 1970 published list. This is unusual because there are other exhibitions included in the list to which Kahnweiler submitted only a selection of artists.

The omission may have been motivated by the fact that each exhibition defied his principles of having his artists neither presented at the salons nor at local events in general, but since the list was published anonymously, the question of who omitted the information in the first place remains unanswered.[50] It is worth pointing out that the expositions in Lyon included two paintings by Picasso lent by Vollard—the Rose period La Coiffure (1906; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and the cubist The Accordionist (1911; The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York).[51] As a result, a cubist Picasso came to hang within close proximity to work by Gleizes and Metzinger among others in a public exhibition in France. Both in the salon and the world’s fair, Kahnweiler engaged in local exhibitions before the war, and while he nonetheless held on to his policy of exclusivity, it is tempting to think that a shift was under way.[52] Could these loans in 1913/14 be an indication of Kahnweiler considering the possibility of supplying exhibitions within France, now that his artists had established themselves on the merit of their respective practices—and that it was only the onset of war that halted this development? In any case, whether of his own accord or because he was urged to do so, Braque made a stopover in Lyon on his way to Sorgues, where he had plans to reunite with Picasso.[53] He must have told his wife Marcelle about his intention, because she followed up with him about his itinerary on June 30: “At the exhibition in Lyon will you go see the pictures by Picasso?”[54] As Braque reported to Kahnweiler the following month, “the paintings are displayed with much taste.”[55]

The third and final example selected here illustrates how the record more concretely underscores Kahnweiler’s promotion of all his artists in equal measure. The record makes plain, for instance, that Kahnweiler continued to promote Van Dongen long after the two had parted ways over what the dealer termed the artist’s turn towards “fashionable portraiture.”[56] As mentioned in the previous section, the last entry for a painting by Van Dongen is numbered “691” (O35). The last solo exhibition Kahnweiler dispatched in May 1914 was also exclusively devoted to Van Dongen. The dealer sent forty-two of his paintings to Richter in Dresden, of which nineteen were marked as sold (Y111–13). The other twenty-three appear to have remained in Germany, for no date of their return is given in the record. According to the record, Kahnweiler sold five Van Dongens at exhibitions prior to May (Y4, Y15, Y35, and Y91). This, in turn, provides a partial explanation to why, of the altogether 140 Van Dongens which Kahnweiler purchased between the spring of 1907 and the spring of 1911, only twenty-nine are documented as included in the Galerie Kahnweiler sequestration sales which took place in the early 1920s in Paris. More on this point below.

In terms of other artists, the record also illustrates that as soon as Kahnweiler reached agreements with Gris, Léger, and Manolo, he immediately dispatched their artwork to exhibitions in Budapest and Prague, and in the case of Léger, to the art dealer Alfred Flechtheim in Düsseldorf between 1912 and 1913 (Y24 for Manolo, Y63 for Gris, and Y74 for Léger). Of these, Gris’s Head of a Woman (Portrait of the Artist’s Mother) (1912) and Léger’s Houses under the Trees (1913), both in the Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, had each returned to Paris from their respective travels by early 1914. Together with the rest of the Galerie Kahnweiler stock, in December of that year, the French state confiscated both paintings as enemy property and eventually included them in the aforementioned sequestration sales.

While Kahnweiler’s strong sense of parity ensured his artists’ equal representation abroad and among established and new clientele, his business sense was also a determining factor in his decision-making. Two telling but lesser-known examples concern the centennial exhibition of French painting in Saint Petersburg in 1912 and the Internationale Ausstellung in Bremen in 1914. In the case of the former, Kahnweiler submitted only two paintings each for Derain and Vlaminck (Y17). Indeed, further research is required to understand Kahnweiler’s motivations in supplying this project with his stock. The organizers intended for the exhibition to focus exclusively on the nineteenth century up to the present and explained, “we purposefully refused the new artists, whose creating belongs to the 20th century. We also excluded a few artists, who, although they work in France, by nationality and painting character, do not belong to the French school, for example, Stevens, Van Gogh, Picasso and others.”[57] An answer to the question of Braque’s exclusion falls outside the purview of this analysis, but it goes to show that each of these exhibitions followed their own logic requiring Kahnweiler’s case-by-case management. Held between February 1 and March 31, 1914, the Bremen exhibition assumed a similar chronological arc, but with a more inclusive outlook as indicated in the title. Although Braque, Derain, Manolo, Picasso, and Vlaminck were all included, Kahnweiler personally supplied only works by Derain, Manolo, and Vlaminck (Y92).[58] In doing so, he may have relied on the successes his artists had already achieved in the region—in the case of Braque and Picasso, their presence was ensured by way of loans from the Aachen-based collector Edwin Suermondt. While the art dealer’s expansion strategy had begun to bear fruit, by that summer, all came to an abrupt halt at the onset of the Great War.

The Yellow Notebook: Rebuilding His Art Business

Just over twenty pages in the Field transcription cover the period between March 1919 and September 1920, showing at least in part how Kahnweiler rebuilt himself toward the end of his exile in Switzerland and immediately after his return to Paris (Y114–35). During this period, documented shipments were no longer just from and to Paris but involved more complex routes and transactions. As the record documents, Kahnweiler revived his contacts with J.H. de Bois in Haarlem, The Netherlands, Michael Brenner and Robert J. Coady in New York, Georg Caspari in Munich, Otto Feldmann in Berlin, Flechtheim in Düsseldorf, Arthur Goldschmidt in Frankfurt, Gottfried Tanner in Zürich, and Léopold Zborowski, then in London. With some of them, such as Feldmann and Brenner and Coady, he arranged for shipments made on his request. With others such as the publisher Georg Biermann and the critic Otto Grautoff, as well as the editorial office of Delphin-Verlag, he shared photographic reproductions. With these last two arrangements, the record helps to clarify that Kahnweiler had access to at least some of his photo albums upon his return to Paris in February 1920. While Biermann selected Kahnweiler’s essays on Derain and Vlaminck for the small book series “Junge Kunst,” co-edited with Werner Klinkhardt in 1920, the latter would publish the dealer’s book Der Weg zum Kubismus that same year.[59] In each of these instances, Kahnweiler’s strategy of having his stock systematically photographed worked again in his favor. Kahnweiler also rekindled relationships with such clients as the Bloch family in Paris and Jan Eisenloeffel in Amsterdam.

Finally, the record confirms that Kahnweiler relied heavily on his prewar art market network to revive his business while at the same time he engaged in expanding his pool of partners. There was Feldmann with whom some of his stock had been left involuntarily at the war’s onset. As Kahnweiler explained to Derain, he had been forced to feign his own death in order to protect the artworks on deposit with his associates outside of France.[60] One case in point concerns a group of thirty artworks by Braque, Derain, Gris, Manolo, Van Dongen, and Vlaminck, which Feldmann kept in Germany (Y114–6). (Fig. 10) The lot, which included artwork deposited with the Berlin art dealer as early as 1912 (Y29), made its way to Flechtheim’s gallery in Düsseldorf at the end of April 1919. Reviving a business was not only Kahnweiler’s concern—Flechtheim, too, had to reestablish himself. The two joined forces, with the shipment from Feldmann arriving on the heels of Flechtheim’s reopening exhibition in Düsseldorf that month.[61] Feldmann, who had been less fortunate than Flechtheim and Kahnweiler, never reopened his business.

The record reveals that André Simon (André Cahen), Kahnweiler’s silent partner in his next gallery, operated on Kahnweiler’s behalf in France since at least the fall 1919 (Y118), while Kahnweiler was still in Switzerland. An untitled and unidentifiable painting by Gris with the inventory number “5000” and seventeen works by Vlaminck with the inventory numbers “5001” through “5016” initiated the new era for Kahnweiler’s art business, when in October 1919, from his exile in Bern, Kahnweiler arranged for a shipment of the Gris and eight Vlamincks to Gottfried Tanner in Zürich (Y117) while Simon, on the other hand, promised seven of the remaining Vlamincks to Flechtheim in Düsseldorf soon after (Y118).[62] The record provides no information on the departing city for each dispatch but with both artists based in Paris, it is reasonable to assume Simon’s assistance with the inventory process and also individual shipments. What can be concluded from the evidence on the artworks themselves is that while the business restarted, the protocol was still very much a work in progress. In the case of Gris’s The Bottle of Banyuls (1914; Hermann and Margrit Rupf-Stiftung, Kunstmuseum Bern), a collage purchased by Hermann Rupf, Kahnweiler’s Bernese friend, in Switzerland, the inventory number “5025” is merely inscribed on the stretcher without a label. (Fig. 11) Still Life with Grapes (1914; Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe), on the other hand, today features the gallery's label, stamped "5021," on the verso. (Fig. 12) Like that of other Kahnweiler artists, Gris’ support proved essential to the successful resurrection of the art dealer’s business. In October 1919, the artist turned over The Bottle of Banyuls and Still Life with Grapes as part of a group of twelve works he had reserved for Kahnweiler during the war, a transaction noted by Field (O back endpaper).[63] Unlike The Bottle of Banyuls, which stayed with its new owner Rupf, Still Life with Grapes, eventually returned to Paris where it became fully integrated in the gallery's stock. According to a Derain and a Vlaminck numbered “6143” and “6148?” (Y123) respectively, it appears that by May 1920, Kahnweiler had amassed nearly 150 new and recuperated artworks. By this time, the art dealer was amid turning a new chapter for himself. He teamed up with Simon to open a new gallery in Paris and forged an alliance with Flechtheim in Germany, with Kahnweiler’s brother Gustav also playing a role (Y125).[64] With his next art business in place prior to opening its physical gallery space at 29 bis rue d’Astorg in September 1920, the new inventory number sequence became the official Galerie Simon inventory.

Another case of how Kahnweiler’s initial stock survived the sequestration is the artist duo Brenner and Coady’s Washington Square Gallery in New York. Their contract with Kahnweiler dated to February 1, 1914, and although it only stipulated the exclusive representation of Braque, Gris, Léger, and Picasso in North America, the three prewar shipments documented in the record included work by Derain, Manolo, Van Dongen and Vlaminck (Y100, Y103, Y105, and Y109). From these, a small selection of ten works came back into Kahnweiler’s hands in June 1920 (Y130). Notably, it included one of only a few Picassos listed in the postwar section of the record. It was the artist’s 1912 cubist still life Fêtes de Céret (private collection, Switzerland; Z II, pt. 1: 319), Galerie Kahnweiler inventory number “1232” (O62), that was included in the return shipment from Brenner and Coady.

If Picasso’s work was rarely part of these early postwar dispatches, it was for reasons Kahnweiler had little control over. The artist and his dealer had fallen out over unmet securities and payments stipulated in their 1912 contract that Kahnweiler owed due to the turmoil at the onset of the war. Despite Kahnweiler’s efforts, their reconciliation did not take place until a few years later.[65] The incorporation of Picasso’s Fêtes de Céret into Kahnweiler’s new gallery venture in the early 1920s resulted in the painting receiving a new inventory number: “613[3?]” (Y130). However, its photo number, “255,” remained unchanged.[66] Initially valued at 1,000 French francs (O62), its price had increased to either 11,000 French francs or German marks when Kahnweiler brought the painting back onto the market together with Flechtheim in the fall of 1921, when it came on view during the opening exhibition of the latter’s new Berlin venue.[67] To put these prices in context, during the first Galerie Kahnweiler sequestration sale that summer, numerous Picasso still lifes achieved the median hammer price of 1,320 French francs.[68] By no later than 1924–25, Fêtes de Céret entered the collection of Gottlieb Friedrich Reber, Picasso’s newest champion and collector, and a close acquaintance of Flechtheim.[69]

Finally, the last section of the record also reveals that with his mind set on rebuilding his business, Kahnweiler had also begun to sign agreements with the next generation of his artists, specifically Henri Laurens. The artist became a part of Kahnweiler’s Galerie Simon roster in April 1920 and by August five of his works on paper made their way to Flechtheim in Düsseldorf (Y132).[70]

Insights Gained

If Kahnweiler became the dealer of cubism it is due not only because this artistic expression literally announced itself to the public at his gallery with Braque’s 1908 exhibition but also because cubism eventually prevailed as more pivotal in the minds of the art historians and critics who first wrote his story. How the art dealer also became so defined by Picasso has to do with their reconciliation and lasting partnership but also with the fact that Picasso ultimately became by far the most famous among Kahnweiler’s artists. The analysis’ objective was to show ways in which these and other preexisting notions can be examined afresh with the aid of the stock book and record of shipments abroad by way of Field’s 1969 transcriptions, and thus revise and deepen the current understanding of Kahnweiler. To this end, it points out some of the new broader insights to be gained from examining this material. For example, the information contained in the outset of the stock book establishes how Kahnweiler swiftly assembled his cohort of artists from a large set of potential candidates. The material explicates how once he had arrived at his selection, he promoted them in exhibitions in equal measure and further afield than previously recognized. The material brings to the fore Kahnweiler’s absolute parity when it came to his artists, be it through acquisitions or circulation of their work. The last section of the record of shipments abroad, on the other hand, reveals that recovering his business and the market for modern art after the war involved Kahnweiler retaking possession of his stock held by his affiliates outside of France in addition to immediately mobilizing his Parisian network. The record thus provides new insights into the earliest days of his new, second art enterprise, the Galerie Simon. Finally, scrutinizing the information in the Field transcriptions alongside such primary sources as correspondence allows to at last piece to together what motivated Kahnweiler to sign written contracts with his artists towards the end of 1912. Until then, the art dealer had regarded contracts as “the exception and not the rule,” but as the critical and commercial success of his artists grew, it became clear to all parties that written statements of expectations would better serve their respective interests.[71] The difference in language in each case indicates that these interests were as much about reciprocal business securities as about the support of all of the artistic practices that Kahnweiler championed as the art of tomorrow.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank John Field for his trust, generosity, and shared passion for art and archival research. Our appreciation also goes to the peer reviewer for valuable feedback on an earlier draft of our analysis.

[1] Even when such a rigorous process was applied to the material available up to now, errors were inevitable, as the present authors have learned.

[2] Kahnweiler, Daniel-Henry and Francis Crémieux. My Galleries and Painters. 1961. MFA Publications, 2003, p. 22.

[3] Assouline, Pierre. L’Homme de l’art: D.-H. Kahnweiler (1884-1979). 1988. p. 83.

[4] Kahnweiler, Daniel-Henry. Letter to John H. Field. 9 July 1966; and Field, John H. Letter to his father, William H. Field. 6 August 1966. Unless otherwise noted, all correspondence and archival documentation are in the John H. Field Papers and Library.

[5] Ibid. (Field, letter to his father).

[6] Field, John H. Draft letter to Anthony Blunt. 1960s.

[7] Field, John H. Draft letter to Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. 1969; and Kahnweiler, Daniel-Henry. Letter to John H. Field. September 9, 1969.

[8] Hommage à Kahnweiler. Pfalzgalerie Kaiserslautern, 1970.

[9] “Von Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler beschickte Ausstellungen 1910-1914.” Hommage à Kahnweiler, p. 67–71.

[10] The authors’ conversation with Field, John H., 2024.

[11] Field, John H. “Picasso & German Collectors, Dealers & Exhibitions up to World War I.” ca. 1988. Unpublished manuscript, pp. 1–32.

[12] Note 3.

[13] Karmel, Pepe. “Picasso and Braque in the Galerie Kahnweiler Files. A Research Document.” 1991. Unpublished manuscript. Karmel examined the stock book and the related photo albums.

[14] Field, John H. Draft letter to John Richardson. 27 June 1991; and Richardson, John, and Marilyn McCully. A Life of Picasso, 1881–1906. 1991.

[15] Richardson, John. “Picasso und Deutschland vor 1914.” Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts. 20 Jahre Wittrock Kunsthandel. 20 Werke. 1994.; and Richardson, John and Marilyn McCully. A Life of Picasso, 1907–1917. 1996.

[16] Richardson, John. “Picasso und Deutschland vor 1914.” Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts. 20 Jahre Wittrock Kunsthandel. 20 Werke. 1994. p. 16 and 32, note 14; and Richardson, John and Marilyn McCully. A Life of Picasso, 1907–1917. 1996, p. viii.

[17] It appears that Kahnweiler did not prepare a photo album for Van Dongen. The sequence for Manolo was 4001-5000. Donation Louise et Michel Leiris. Collection Kahnweiler-Leiris, 1984–85, p. 129.

[18] Additional works in this group that can be identified based on recorded Galerie Kahnweiler inventory and/or photo numbers are: Inventory number 931: Gueridon, 1912 (Romilly 132); 932: Homage to J. S. Bach, 1912 (Romilly 122); 936: The Bottle of Bass, 1911–12 (Romilly 118); and 938: Gueridon, 1911 (Romilly 97). Worms de Romilly, Nicole, and Jean Laude. Braque. Le Cubisme: Fin 1907–1914. 1982. Pepe Karmel tentatively identified inventory number 933 as Glass and Bottle, 1912, (Romilly 120). Note 13. Inventory number 937, a work on paper, remains unidentified to date.

[19] Jozefacka, Anna, and Luise Mahler. “Catalogue of the Collection.” Cubism: Leonard A. Lauder Collection, edited by Emily Braun and Rebecca A. Rabinow et al., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014, p. 254, no. 14. Scholars and conservators identified the possibility of more than one painting campaign as early as the late 1950s. The confirmation of the Galerie Kahnweiler inventory number further supports this theory, but conservation analysis is required to determine the stylistic evolution of the painting since 1912.

[20] While the Galerie Kahnweiler label adhered to the painting’s center stretcher bar does not feature the customarily stamped inventory number, a separate handwritten period label identifies the title as documented in the record of shipments abroad: “Le panier de poissons [sic]”. Thanks is owed to Cathy Herbert.

[21] Daix, Pierre and Joan Rosselet. Le Cubisme de Picasso: Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint, 1907–1916. 1979, p. 205, no. 77.

[22] Monod-Fontaine, Isabelle. “Chronologie et documents.” Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler: marchand, éditeur, écrivain. 1984, p. 95. Also listed is “Braque (?)” as a possible purchase at the salon.

[23] Catalogue de la 23me exposition. Société des Artistes Indépendants. 1907. For Edvard Diriks, p. 102, no. 1564; Charles Guérin, p. 138, no. 2179; and Francis Jourdain, p. 163, no. 2592.

[24] Charles Camoin, peintures et dessins. 6–18 April 1908 ; and Peintures de Pierre Girieud. Grès de Franscisco Durio. 26 October–14 November 1908.

[25] The Galerie Kahnweiler inventory number “1202” is not documented in the artist’s catalogue raisonné. Moreover, the catalogue raisonné lists the number “454” as associated with Kahnweiler for the 1912 painting Banjo and Glasses (Morton G. Neuman, Chicago) but fails to clarify that this number corresponds to a Galerie Simon and not a Galerie Kahnweiler inventory number. For the Galerie Kahnweiler inventory number “454,” see O23. For Banjo and Glasses, see Cooper, Douglas and Margeret Potter. Juan Gris: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings. 2014, p. 41, note 21.

[26] Donation Louise et Michel Leiris. Collection Kahnweiler-Leiris, p. 114.

[27] Kahnweiler, Daniel-Henry and Francis Crémieux. My Galleries and Painters. 1961. MFA Publications, 2003, p. 45.

[28] Richardson, John, and Marilyn McCully. A Life of Picasso, 1907–1917. 1996, p. 285.

[29] Debray, Cécile. “Gertrude Stein and Painting: From Picasso to Picabia.” The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso and the Parisian Avant-Garde. Edited by Janet C. Bishop et al., 2011, p. 240, note 12, and p. 433, no. 264.

[30] The Flowers of Friendship. Letters written to Gertrude Stein. Edited by Donald Gallup, 1953, pp. 86–7.

[31] Karmel was the first to suggest the existence of a hypothetical second inventory book. Note 13.

[32] Worms de Romilly, Nicole, and Jean Laude. Braque. Le Cubisme: fin 1907–1914. 1982, no. 246, p. 290.

[33] Assouline, Pierre. L’Homme de l’art: D.-H. Kahnweiler (1884-1979). 1988, pp. 60–1. The authors’ translation.

[34] The exhibitions took place in February–March and July–October 1910 respectively, but because Kahnweiler did not document his shipments separately until October 1910, these earliest exhibitions are not listed in the record of shipments abroad. Of the two, only the Düsseldorf one is cursorily mentioned (Y1). See Jozefacka, Anna and Luise Mahler. “Cubism Goes East: Kahnweiler’s Central European Network of Agents and Collectors.” Years of Disarray, 1908–1928: Avant-gardes in Central Europe. Karel Srp et al., Olomouc, Muzeum umění, 2018, pp. 59–61.

[35]Neue Künstlervereinigung München E.V., Turnus 1910–1911, II. Ausstellung was on view from 1–14 September 1910, and therefore overlapped with that year’s Sonderbund exhibition in Düsseldorf.

[36] See also Jozefacka, Anna, and Luise Mahler. “Cubism Goes East: Kahnweiler’s Central European Network of Agents and Collectors.” Years of Disarray, 1908–1928: Avant-gardes in Central Europe. Karel Srp et al., Olomouc, Muzeum umění, 2018, pp. 56–69.

[37] Richardson, John, and Marilyn McCully. A Life of Picasso, 1907–1917. 1996, no. 60, p. 468.

[38] Note 9. Since the list was published anonymously, it cannot be known who authorized the omissions. It also cannot be easily explained why errors were made, if Kahnweiler was indeed the one who drew up the list.

[39] Picasso, Pablo. Letter to Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. 15 July 1912. Quoted in Christian Geelhaar, Picasso: Wegbereiter und Förderer seines Aufstiegs, 1899–1939. 1993, pp. 47, 274, note 134.

[40] Braque, Georges. Letter to Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. 16 September 1912. Quoted in Cousins, Judith, and Pierre Daix. “Documentary Chronology.” 1989, p. 403.

[41] See van Adrichem, Jan. “The Introduction of Modern Art in Holland, Picasso as pars pro toto, 1910-30.” Simiolus vol. 21, no. 3, 1992, pp. 162–211, especially pp. 177–180.

[42] The painting is visible in an installation photograph. Ibid., p. 178, fig. 17. It is not known to have ever entered Kahnweiler’s stock.

[43] Braque, Georges. Letters to Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. 19 or 26 September and 27 September 1912, respectively. Quoted in Cousins, Judith, and Pierre Daix. “Documentary Chronology.” 1989, pp. 404–5.

[44] Isarlov, George. Georges Braque. 1932, pp. 29–30.

[45] Von Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler beschickte Ausstellungen 1910-1914.” Hommage à Kahnweiler. p. 70.

[46] Emil Richter organized at least three exhibitions at his gallery between March and May 1914: Henry Valensi, Hermann Prell, and the Künstlervereinigung Dresden. While it is possible that some if not all works came on display at the gallery at some point during this time, the programming and the lack of any reviews in the period literature suggest otherwise.

[47] The 1907 Salon d’Automne catalogue credits the work of Derain and Othon Friesz as from the dealer. Monod-Fontaine, Isabelle. “Chronologie et documents.” Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler: marchand, éditeur, écrivain. 1984, p. 97.

[48] See Stuccilli, Jean-Christophe. “Lyon, ‘Boulevard de la peinture nouvelle’? Van Dongen, Matisse, Picasso et les autres …." Lyon, Centre du monde! L’Exposition internationale urbaine de 1914. Musées Gadagne de la Ville de Lyon, 2013, pp. 293–305.

[49] Exposition Internationale 1914: Beaux-Arts. Ville de Lyon, 1914, pp. 18, 39, nos. 142–3 and 416–8, respectively.

[50] Note 9.

[51] Exposition Internationale 1914: Beaux-Arts. 1914, p. 32, nos. 333–4. The former is reproduced in the exhibition catalogue, the latter is identified in Cousins, Judith, and Pierre Daix. “Documentary Chronology.” 1989, p. 430. Subsequently, an examination of the Accordionist revealed an Ambroise Vollard inventory number (“3893”), which is inscribed on the central vertical stretcher bar in blue crayon. Thanks is owed to Julie Barton.

[52] Richardson emphasized that Picasso “liked the reclusive image that Kahnweiler devised for him.” Richardson, John, and Marilyn McCully. A Life of Picasso, 1907–1917. 1996, p. 301.

[53] Unlike Picasso, who found gallery representation in Berthe Weill, Clovis Sagot, and Vollard prior to meeting Kahnweiler, Braque had shown primarily at the salons, which meant that his work circulated primarily out of his studio.

[54] Cousins, Judith, and Pierre Daix. “Documentary Chronology.” 1989, pp. 428–9.

[55] Braque, Georges. Letter to Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. 15 July 1914. Quoted in Cousins, Judith, and Pierre Daix. “Documentary Chronology.” 1989, p. 429.

[56] Note 26.

[57] “[Vy'stavka sto let franczuzskoj zhivopisi (1812-1912): Exhibition 100 Years of French Painting (1812-1912)].” In Database of Modern Exhibitions (DoME). European Paintings and Drawings 1905-1915. https://exhibitions.univie.ac.at/exhibition/411. Accessed May 27, 2025.

[58] Internationale Ausstellung. Kunsthalle Bremen, 1914. Catalogue nos. 101–2, 362–3, and 667–71 respectively.

[59] See Daniel Henry [Kahnweiler], André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, both Verlag von Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1920; and Der Weg zum Kubismus, Delphin Verlag, 1920.

[60] Kahnweiler, Daniel-Henry. Letter to André Derain. September 6, 1919. See Monod-Fontaine, p. 123.

[61] Titled “Wiedereröffnung–Ostern 1919: 1. Ausstellung,” the exhibition ran from April 20 to mid-May 1919 but, as far as can be established, did not include any of the artwork from the Feldmann lot. Subsequent exhibitions, on the other hand, each contained individual works by, for example, Derain, Gris, and Manolo. See the checklists reprinted in Ottfried Dascher, “Es ist was Wahnsinniges mit der Kunst": Alfred Flechtheim: Sammler, Kunsthändler und Verleger, 2011, pp. 53–55 and 59–63.

[62] The inventory numbers “8000” and “8017” listed on the subsequent page (Y118) are outliers. They are either incorrect or were possibly copied incorrectly by Field.

[63] Cooper, Douglas, Letters of Juan Gris, 1956, letter LXXXIII, p. 69.

[64] Judging by the shipment of Kahnweiler’s stock from Feldmann to Flechtheim (Y114–6), Kahnweiler and Flechtheim were in touch again already by at least April 1919.

[65] Despite his efforts, it took until 1923 for Kahnweiler to again acquire work directly from Picasso. Kahnweiler, Daniel-Henry. Letter to Pablo Picasso. February 10, 1920. Quoted in Richardson, John, and Marilyn McCully. A Life of Picasso, 1907–1917. 1996, p. 358. Kahnweiler, Daniel-Henry. Letter to Alfred Flechtheim. April 23, 1923. Quoted in Flacke-Knoch, Monika, and Stephan von Wiese, „Der Lebensfilm von Alfred Flechtheim,“ 1987, p. 173.

[66] After the war, Kahnweiler resumed the photo number sequences he had devised in 1910 and assigned the next closest consecutive number as new work came in. For example, Braque’s Glass and Ace of Clubs (1919; Hermann and Margrit Rupf-Stiftung, Kunstmuseum Bern) received the photo number “1215,” which was four numbers up from the last entry in his prewar photo album for Braque. Isarlov, 1932, pp. 20 – 21, esp. nos. 203 and 238.

[67] Kahnweiler, Daniel-Henry. Letter to Alfred Flechtheim. September 9, 1921. Transcription by Stephan von Wiese, ca. 1987, p. 27; and Eröffnungs-Ausstellung Deutsche und französische Kunst aus des XX. Jahrhunderts, exh. pamphlet, Galerie Flechtheim, Berlin, early October 1921, unpaginated, no. 91, as Stilleben mit Festprogramm.

[68] The hammer prices are documented in an annotated copy of the June 13–14, 1921 Catalogue des tableaux, gouaches, & dessins (First Galerie Kahnweiler sale) held at Thomas J. Watson Library at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.