Picasso, UNESCO and The Fall of Icarus

Ce texte est issu de la séance du symposium Célébration Picasso intitulée "Picasso et l'Unesco" qui s'est tenue à l'Unesco le 8 décembre 2023.

In October 1955, Pablo Picasso was offered the opportunity to create a large mural for the new headquarters in Paris of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. He informally accepted the commission, then appeared to waver, but eventually signed a contract and proceeded to deliver a formidable wall-painting, known as The Fall of Icarus [fig. 1] installed in time for the official opening of the new buildings in November 1958. Fixed and sheltered at the heart of the UNESCO complex, the huge painting has not featured in gallery or museum exhibitions, can only be seen by the public on pre-booked guided tours, and it has been the subject of relatively few publications. Study and discussion of that painting will be the main focus of interest here. The institutional commissioning of an artwork by Picasso was, in France, however, a rare occurrence, and Picasso himself always resisted the constraints that working to order implied. Archive documents and other sources will here allow us first to map the circumstances which led to the award of this particular and prestigious commission. While following the contacts between Picasso and UNESCO personnel, we will also seek to define the politics of his decidedly distant relationship with the institution itself[1].

Picasso and UNESCO Decision-Making

UNESCO was founded in 1945, shortly after the creation of the United Nations Organisation, whose founding Charter was signed by fifty nations, not including the Soviet Union, which joined in 1954, after the death of Joseph Stalin. Once it was agreed that UNESCO’s headquarters should be sited in Paris, the organisation was provisionally housed on avenue Kléber, not far from the Arc de Triomphe, in the huge Hôtel Majestic, property of the French State since 1936. When UNESCO’s new permanent premises opened in 1958, they included two interconnected main buildings, the seven-storey Secretariat and the Conference Building. Picasso’s mural was to be sited in the Delegates’ Foyer of the Conference Building.

During the planning and construction of the new buildings, strategic decisions were taken by UNESCO’s Headquarters Committee, while an Architecture Committee had oversight of specifically architectural matters. Also known as “the Panel of Five architects”, it was headed by Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, and included Le Corbusier. UNESCO’s Director General usually followed recommendations from the experts, but he had final say. In June 1953, the 11th session of the Headquarters Committee was devoted to “Gifts and Works of Art”. It was noted that “42,400,000 francs had been provided for commissioning works of art from painters and sculptors”, and that UNESCO now needed a Committee of Art Advisers[2]. A follow-up report from the Headquarters Committee then collated decisions that would underpin the building project. These included the site of the new headquarters, a disaffected cavalry barracks (Caserne Fontenoy) in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, opposite the École militaire, offered to UNESCO by the French government on a renewable 99-year lease, for a symbolic annual rent of one thousand francs. Design, material and construction costs were to be covered by a governmental, thirty-year, interest-free loan of six million dollars (over two thousand million French francs). On the recommendation of the Architecture Committee, it had been decided in 1952 to award the project to a trio of American, Italian and French architects, all internationally renowned and resolutely modernist: Marcel Breuer, Pier Luigi Nervi and Bernard Zehrfuss. A Committee of Artistic Advisers (the CAA) would ensure the “harmonious integration of decorative elements into the architectural whole”, would also establish a list of major works to be commissioned and would identify their recommended artists. The provisional date for completion of the headquarters was optimistically set at 1st March 1956[3]. In other words, from the outset, UNESCO envisaged an overtly modernist headquarters in which contemporary art and architecture would be intimately connected, in line with the theories of the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier[4].

The CAA would be presided by Caracciolo Parra-Pérez, a historian, politician and diplomat, Venezuelan Ambassador to UNESCO. Other members included Georges Salles, Director of the Museums of France from 1945 to 1957, when he became President of UNESCO’s International Council of Museums; Sir Herbert Read, English art historian, philosopher, poet and erstwhile surrealist; Francisco Sanchez Cantón, Deputy-Director of the Prado Museum, a specialist on 16th and 17th-century Spanish painting; and Shahid Suwardy, a Pakistani politician and Islamic art expert. Working in collaboration with the architects, Read and Salles would be the most influentially active members of the team. Salles knew Picasso well. In 1947, for example, he and Jean Cassou had initiated and facilitated Picasso’s gift of ten major paintings to France’s new Museum of Modern Art and he later supported Picasso’s desire to see his War and Peace chapel in Vallauris recognised as a French National Museum (finally inaugurated in 1959)[5]. Salles also worked very effectively with Zehrfuss, the youngest of the UNESCO architects and the only one of the three who was permanently based in Paris.

The CCA’s first meeting took place in Paris, 16-18 May 1955. In consultation with the architects, the CCA identified sites in the planned buildings and grounds suitable for six key works of art. They also agreed that one of the sites, the large wall planned for the Conference Building, offered “a unique opportunity for commissioning a work by one of the great masters of contemporary art.” For each commission, they established a list of three artists, in order of preference, to be submitted to the Director General, the only exception being a giant mobile sculpture, for which the only possible choice was Alexander Calder. Their six preferred artists were Jean Arp, Calder, Juan Miró, Henry Moore, Isamu Noguchi and Picasso. Picasso was recommended for the Conference Building foyer wall-painting, ahead of second and third choices Miró and Fernand Léger. It was also agreed that works by younger artists of other nationalities should eventually be sought for the canteen, terrace and other spaces on the Secretariat’s seventh floor. It was, however, noted that the artwork budget, amounting to 121,000 dollars, was only about 2% of the total construction budget and was insufficient, given the quality and prestige of the artists envisaged[6].

The CCA’s first choices were eventually accepted by the Director General. Salles then travelled to Cannes, where Picasso had settled in “La Californie”, an imposing 1920s villa. From his hotel, in a letter dated 30 October 1955, Salles asked Picasso if he would agree to make a 10 x 9 metre wall-painting for the Conference Building in the new “palais de l’UNESCO”, currently under construction. He added that it would obviously be the most important artwork in the building, and that Miró, Moore, Arp and Calder had already agreed to participate[7]. That letter would initiate two years of uncertainty, punctuated by several key events.

In November 1955, at the second meeting of the CCA, Salles reported that he had obtained “acceptance in principle” from Arp, Miró, Moore and Picasso. Breuer reported that Noguchi had also accepted by telephone a commission for a sculpture-garden. Reiterating the inadequacy of their budget, the CCA also stipulated the provisional fee payable to each artist. Arp, Calder and Noguchi would be offered 5,000 dollars each (in 2024 equivalent to $55,500). Miró, Moore and Picasso would be offered 10,000 dollars each. UNESCO would also cover costs of materials, transport and installation[8]. The CCA fee and costs recommendations were accepted by the Secretary General. Determined to see the overall project delivered within budget, he would nevertheless also concede an extra 70,000 dollars for art commissions[9].

The UNESCO Director General from 1953 to 1958 was Luther Evans. He was a Texan and a political scientist, who left academia to become Head of the Library of Congress in Washington D.C., before taking over at UNESCO. He arrived in Paris with multilingual skills, faith in the value of education and a track-record of managerial efficiency. He also, however, brought political baggage. At the library, inspired by Joseph McCarthy and President Truman’s Federal Employee Loyalty Program of 1947, Evans had established a Loyalty Board, intended to remove communists and homosexuals among his staff. As a result, numerous library employees resigned or were dismissed[10]. At UNESCO in Paris, Evans similarly screened all US citizens serving at the institution, dismissing seven of them because by objecting to the investigation, they allegedly cast “reasonable doubt” on their loyalty to the USA[11]. At the height of the Cold War, it is likely that this background will have coloured Picasso’s attitude to Evans and even, as we shall see, to[12].

Seeking a Solution

In June 1956, Salles returned to Cannes with Zehrfuss, who gave Picasso a model of the Conference Building[13]. Picasso, however, told them he could not provide a “special maquette” for the UNESCO mural as “the final project would not take into account any of his previous sketches.” In Vallauris, the two visitors nevertheless saw works by Picasso “in ceramic with mythological figures which can be considered as a preliminary project for the decoration of the wall.[14]” So Picasso first intended to use the UNESCO commission to develop his ongoing work at the Madoura pottery in Vallauris. His project would have brought employment and prestige to the working-class town, which had a communist mayor, a pottery-making tradition and the Arnera print-making workshop, where Picasso had acquired and invented linocut techniques. He had in 1949 given Vallauris, for the town square, a bronze cast of his sculpture Man with a Sheep. He was subsequently made an Honorary Citizen of the town and thenceforth did all he could to favour its development. His ceramics solution for the UNESCO project would also have extended his creative dialogue with Matisse, whose Apollo (Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio, USA), made in 1953 in a workshop in Nice, was a wall of tiles, based on a paper cut-out maquette with a mythological theme.

On 1st January 1957, visiting the Côte d’Azur, Zehrfuss had written to Picasso to say he was staying for four more days and requesting an update for the CCA. A meeting of the Headquarters Committee on 16 January 1957 then noted that, although Picasso had made no objection to his proposed fee and costs, he was not answering UNESCO correspondence and Zehrfuss had been unable to meet or contact him[15]. In February 1957, new plans of the Conference Building, with photos of the large interior wall, now completed, were posted to Picasso[16]. In March, Salles informed the CAA that Picasso had “abandoned the ceramics idea in favour of a mural in oil-paint. It will be made in his studio on Isorel panels.[17]” Picasso had previously used Isorel, a flexible, composite hardboard, for his War and Peace chapel. This news triggered a further visit to Picasso by a UNESCO delegation, but they found him apparently preoccupied and undecided. On the front of his villa, they helpfully outlined the size of the mural, which only alarmed the artist, who declared, “I’m no longer twenty-five, it can’t be done.” When they suggested he could provide a design to be upscaled by a scene-painter or mural specialist, Picasso rejected the idea, insisting, “I want to live this picture myself, just as I do all my other paintings, otherwise it will become a mere decoration.” To close the proceedings, Picasso wished them all “Au revoir!”, while conceding, “There is a solution, but I must find it myself.[18]” It was still game on, but whereas UNESCO documents consistently refer to the décoration of the new buildings, Picasso specifically rejected that term. Several more months would pass before he could focus on the UNESCO project.

In autumn 1957, Henri Laugier intervened to disrupt the apparent log-jam. An eminent physiologist, Laugier was an army medic during the First World War, was in 1939 the founding Director of the CNRS, a Resistance activist from June 1940, then Deputy General Secretary of the United Nations in New York, before returning to France in 1951 to work in government. In 1958, he was a serving member of UNESCO’s board of management. He had known and admired Picasso and his work since the 1920s, and in 1940 had used his leverage at the Ministry of Justice to support the artist’s abortive application for French nationality[19]. Laugier’s partner, Marie Cuttoli, had contacted Picasso as early as 1927, when she had a gallery in Paris, on rue Vignon, to suggest making tapestries from his designs. This resulted in two tapestries, The Minotaur and Women at their Toilette, woven in the 1930s, using Picasso’s papier collé and collage designs[20]. Picasso remained on excellent terms with this dynamic couple, who lived near him, in Antibes. In late September 1957, Laugier wrote a letter to an unidentified “dear friend” at UNESCO (probably Zehrfuss), giving details of a plan he had put to Picasso: the Isorel panels for the mural should be assembled within a custom-built, vertical frame to be erected in a suitable workspace somewhere near Picasso’s villa. UNESCO should also find the artist a discreet, technically adept assistant, ready to help with the frame and the panels, run errands, grind pigments and do whatever the artist needed to complete the job. Laugier added, “Picasso is at present in very good form, creatively very active, a magnificent poet of shapes and colours. “You understand, he told me, you know me… Once I get to work, I’ll need a week or a fortnight, no more than that.” (“Picasso est actuellement en pleine forme, en pleine activité créative, magnifiquement poète des formes et des couleurs. “Vous comprenez, m’a-t-il dit, vous me connaissez… Quand je serai au travail il me faudra huit ou quinze jours, pas plus.”)[21]. On 30 September, Zehrfuss wrote to Raoul Erena, an architect based in Nice, asking him, on behalf of UNESCO, to find a local carpenter who could provide Isorel panels, and also someone to be Picasso’s temporary assistant. He should also contact Picasso himself, via Georges Ramier of the Madoura pottery, Laugier or Cuttoli[22].

On 24 October, Jean Thomas, Interim Director General of UNESCO, formally wrote to Picasso. His letter thanks him for agreeing to participate in the décoration of the institution’s new headquarters, in the way he had agreed with Laugier. It also stipulates in French francs the fee Picasso will receive and expresses the fervent hope that the mural will be completed by June 1958. Hernán Vieco, a Colombian colleague of Zehrfuss, working on the UNESCO buildings, was sent immediately to Cannes with this crucial letter, to serve as a contract and to be delivered by hand to Picasso. Vieco travelled down on 28 October and returned to Paris with one copy of the contract-letter duly validated by the artist’s signature. The document bears two words in the artist’s hand: “Agreed / Picasso” (“D’accord / Picasso”). Unusually, and emphatically, the artist double-underlined his signature[23].

Vieco wrote an official Report, dated 7 November 1957, regarding his visit to Cannes. He noted that during his two days there he met Picasso, Erena and Mr Rapastelli, a local carpenter. Erena agreed to coordinate and supervise manufacture and assembly of the forty panels. Rapastelli provided Vieco with written costings for the panels, to be delivered within three weeks of approval of his estimate. Picasso, for his part, signed the letter-contract on 29 October and stated his intention to work on the mural at home and not in a room at Hotel Martinez[24]. Predictably, Picasso preferred not to have an assistant foisted upon him, and not to make his painting on panels assembled in a huge, vertical frame, in a makeshift workspace at a hotel, even if it was the art-deco Hotel Martinez on Canne’s boulevard de la Croisette. On 6 November 1957, the Rapastelli invoice, for 760,000 francs, was approved by UNESCO’s Pierre Marcel. Picasso must have discussed carpentry with Rapastelli and Erena, because the invoice was not for Isorel, but for wood panels: Picasso would take delivery of forty, laminated mahogany panels, precisely cut to size.

Picasso at Work: Las Meninas, Bathers and Divers

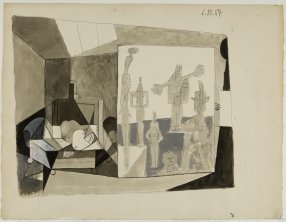

In late September 1957, Laugier had found Picasso in positive mood and vibrantly creative. This was indeed an exceptionally productive time for Picasso and it seems likely that he had shown Laugier the paintings on which he had been working confidentially since mid-August. While colleagues at UNESCO fretted about the mural, Picasso was making his Las Meninas series, which would finally extend from a preparatory drawing to forty-four paintings (Barcelona, Museu Picasso), all of which rearranged, adapted and detailed Diego Velázquez’s 1656 masterpiece (Madrid, The Prado). Only when that series neared its conclusion could Picasso engage with the UNESCO commission. That transition began when he made for the UNESCO project an initial, mixed-media drawing, dated 6 December 1957 [fig. 2]. It represents the artist in his studio, with a reclining nude woman and a painting on an easel[25]. As with Guernica, Picasso launched into this new commission by first drawing his laboratory, the studio where anything may happen. The content of this first drawing was also defined, however, by his intimate familiarity with Las Meninas, in which Velázquez had depicted himself before a canvas on an easel. In his first UNESCO drawings, Picasso chose to transform the royal suite depicted by Velázquez into an artist’s studio, foregrounding the artist’s presence, while retaining a painting on an easel. Whereas Velázquez shows the back of his canvas, Picasso swivelled the easel round to reveal the painting upon it. Thematically related, Picasso’s Las Meninas paintings and his first UNESCO drawings also overlap chronologically: drawings for the UNESCO project began on 6 December 1957, while his Las Meninas series continued to 30 December. As a result of this initial contiguity, there would be traces of Las Meninas DNA in the final UNESCO mural.

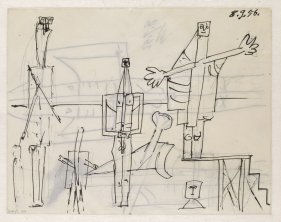

In 1956, Picasso had made The Bathers (Stuttgart, Staatsgalerie), a witty, composite sculpture, constructed from bits of wood and old picture frames, representing six naked figures, flat and viewed frontally, standing by the sea and in the water [fig. 3]. In July 1957, he painted Bathers at La Garoupe (Geneva, Musée d'art et d'histoire), a large canvas on which the same six figures, coloured in woody grey and beige, stand against an expanse of pale blue sea, which rises to a broad strip of white sky. In the painting, the two right-hand bathers stand on a diving-board. In Picasso’s 6 December 1957 drawing, the painting on an easel is recognisably Bathers at La Garoupe. So the imagery of bathers and a diver, present in the final UNESCO mural, was inscribed in the project from its very inception. The reclining female nude in the 6 December drawing would also reappear in the UNESCO painting, sunbathing and seen from another angle, foreshortened.

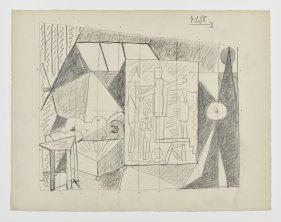

Picasso’s work on drawings for the mural would continue for nearly two months. In all, he produced thirty-four drawings in three sketchbooks [fig. 4], fifty on loose sheets and two preparatory paintings[26]. For over a month he drew multiple variations on the artist’s studio and its contents, topped by a ceiling that slopes down at an angle to match the trapezoidal shape of the wall on which the mural would be fixed [fig. 5]. He also started to experiment with colour combinations. But on 18 January 1958, he moved the bathers outdoors, liberating them from the confines of a painting on an easel and allowing them to spread out across the page. He also removed the diving board, which had indicated a swimming pool environment, so the bathers were now by the sea, at the same time reducing their number and grouping them around a female figure, plunging out of the sky, aerodynamically, like a cormorant. On 25 January he made fifteen drawings of this one figure, a sign of her importance. The series culminated in a drawing Picasso worked on from 18 to 29 January, noting the twelve consecutive dates in the top right-hand corner[27]. Within the outline of a trapezoidal space, he drew and coloured essential elements of his geometrically schematic seascape, on which he moved around a collection of gouache cut-outs, fixed with pins. Reusing the épinglage technique he had first tried in 1913 cubist drawings, he was also referencing works by Matisse, of which the most relevant is The Fall of Icarus, an iconic masterpiece Matisse made in 1943, using pinned paper cut-outs (Private Collection). Matisse’s Icarus is a white figure falling through a well of blackness, against a royal blue background, elements that prefigure Picasso’s final painting[28]. Picasso will probably have seen the lithographic version of that cut-out, printed in 1945 as the frontispiece of the art magazine Verve (a Matisse special issue, volume IV, no. 13). For his part, finally, on 29 January, Picasso’s coloured and pinned drawing arrived at a satisfactory design: using just seven fields of colour, he distributed four naked bathers, one in the water, three on land, around a central skeletal figure, falling headlong towards the sea. That was his blueprint for the UNESCO painting[29] [fig. 6].

In February, Picasso began painting the surfaces and edges of the panels, mainly in groups of four, laid out on the floor of his home workspace. The scale of the mural meant he had to work on one section at a time, with no encompassing overview. “Not easy” (“Pas commode”), he would say later in a Radio UNESCO interview. On 24 March 1958, Pierre Marcel at UNESCO wrote to Erena that he had learned that Picasso’s work on the mural was finished and that Erena would very soon be assembling it to be exhibited in Vallauris[30]. Picasso had indeed decided to endow Vallauris, rather than Paris, with the honour of inaugurating the monumental painting. The chosen date marked the tenth anniversary of his arrival there and corresponded to the southern town’s springtime festival. From Picasso’s point of view, the timing he had engineered was exactly right. The painted and numbered panels were taken from “La Californie” to Vallauris’s Anfosso School Group, to be assembled in the schoolyard, against scaffolding and under a new roof, constructed by local artisans, working extra night-shifts by floodlight in order to finish in time[31].

Vallauris: Vernissage and Handover

There would be two official presentations of the mural in Vallauris, and the first took place on the afternoon of Saturday 29 March. The mayor and town councillors, Picasso’s son Paulo, friends, guests and celebrities, journalists, photographers and a British Pathé News film-crew, gathered in the schoolyard[32]. Picasso himself unveiled the painting and, as he gazed for the first time at his completed work, he was heard to say, “It’s quite good, better than I thought.[33]” George Salles then stepped forward to make a speech in praise of the mural, painted with “the inspirational energy of a rapid sketch” (“l’impulsion de l’inspiration comme dans une esquisse”), and simple as “a great myth from antiquity” (“comme un grand mythe antique”). As for its subject, “It is the fall of an Icarus of darkness, the forces of evil are here vanquished by the forces of light, by those of mankind, present like a choir from antiquity on the right of the picture, contemplating, victorious, on the shore, a peaceful world that they have created.” (“C’est la chute d’un Icare des ténèbres, les forces du mal sont vaincues ici par celles de la lumière, par celles des hommes présents comme un chœur antique à la droite du tableau, contemplant, vainqueurs, sur le rivage un monde en paix qu’ils ont créé.”)[34] Salles’ dithyrambic oration projected onto the painting an optimistically allegorical narrative designed to make it relevant to UNESCO’s ethos and aspirations. A photo by Inge Morath [fig. 7] shows Picasso immediately after the unveiling, alone with his back to the towering painting, right arm outstretched, cap in hand, a torero acknowledging applause. As the bull lies dead, so the painting is finished. Photos by Edward Quinn show Picasso then engulfed by the crowd, smiling broadly, flanked by Jean Cocteau and Maurice Thorez, the French Communist Party leader [fig. 8]. That same evening, Picasso, Jacqueline and several close friends returned to the schoolyard for a private view. Édouard Pignon would recall the silence that fell on the group when the floodlights came on and “suddenly, all the true colours appeared.[35]” Very probably, this was the last time Picasso saw it.

The following Friday, a UNESCO delegation, led by Evans, arrived in Vallauris, with reporters, photographers and film crews, for the formal handover of Picasso’s painting. The Secretary General was apparently “outraged” by the work’s inappropriate display of suggestively naked flesh[36]. Picasso stayed away, supposedly suffering from a cold, and Paulo Picasso took his place at the official handover[37]. The painting was exhibited at the school for two weeks, with tickets priced at 200 francs, to offset costs incurred by the municipality. Disassembled, wrapped and insured, the panels, weighing 500 kilos, were then transported to Paris in three crates, to be kept in storage until the Conference Building was ready. On 28 April 1958, the crates arrived at the Museum of Modern Art’s storage facility, rue de la Manutention[38]. The crates were finally moved to the Conference Building on 19 August[39].

Serenity and Airborne Violence: the X-Ray Icarus

Once installed in the Delegates’ Foyer, the painting, which measures 910 x 1060 cm., could at last be viewed in the setting for which it was intended. The top line of panels perfectly fits the trapezoidal shape of the wall against which they were fixed, sloping downwards from left to right. Variations on that diagonal strikingly recur within the composition. The top of the painting is occupied by a broad, irregular, ivory-white strip, suggesting a layer of clouds, above a blue background that suggests both the sky and the sea, in a transitional space merging air and water. To the right, a brown strip of land is extended by three black, grey and green triangles and a small, angular, sandy beach. Across these flat spaces are distributed the five figures, schematically represented, without receding perspective, on a single plane. The restricted palette, linear style and direct impact indeed bring to mind Picasso’s Vallauris linocuts. The five characters divide the seascape into three parts, occupied, from left to right, by a female bather in the sea; a skeletal diver; two reclining sunbathers, with a standing man. All are naked, so the scene may belong to any era, from antiquity to the present.

Picasso here redeployed the iconography of bathing scenes, notably associated with Cézanne, but he disrupted such models by introducing his central figure, starkly delineated against a surrounding black shadow. The skeletal limbs, elongated by downward velocity, with fingers splayed like claws, reflect Picasso’s interest in the sculptural qualities of animal bones, and recall more specifically the bat skeleton, bleached and attached to a black support, as if crucified, which he displayed in his cabinet of curiosities[40]. Over to the right, the sunbathing woman seems oblivious to surrounding events, the man laconically raised on one elbow appears singularly unmoved by what he sees, while the swimmer on the left is looking away. The contrast between their indifference and the falling figure necessarily calls to mind Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Fall of Icarus (circa 1588). If Picasso, consciously or otherwise, had assimilated that archetype and was here depicting Icarus, then the standing man, transferred from Bathers at La Garoupe, may be interpreted as Daedalus, pale and wringing his hands as his son pays the price for ignoring paternal advice.

This combination of careless serenity and violent intensity places Picasso’s UNESCO painting within a series of his bathing scenes which also depict a potential or unfolding tragedy, typically involving something intrusively falling from the sky. An example would be Bathers (Baigneuses) (Stuttgart, Staatsgalerie), a painting dated 6 September 1932, which shows to the left a female diver plunging vertically towards the sea, where a woman, unaware, is swimming. Two others bathers are flinging themselves towards the right, to escape the diver. Serge Linares has highlighted a larger work (81 X 100 cm.) from later in 1932, Women and Children by the Sea (Sauvetage) (private collection), because it combines seaside bathers with a diver descending vertically from above[41]. This painting also powerfully exemplifies the recurring formal and thematic opposition in Picasso’s bathing scenes between zones of insouciance and violent movement. The beach scene here is joyful, as a mother on the right plays with her children, lifting one high in the air, while another woman, her profile emerging from the water, gently swims by. Dominating the picture, however, a woman in red is calling for help, one arm raised, the other holding a drowned woman. From the top-left corner, the female diver, the length of her body shadowed in black, resembles an angel of death as she plunges towards the drowned woman and her helper. That contrast, the descending diver, the use of oblique lines and triangles, a limited palette and single-plane flatness, indeed make this painting, in 1932 already, a prefiguration of the UNESCO mural. Linares also identifies in the 1958 mural a balance of opposing forces, between the negative pull of the falling figure and “the vertigo of an ascent”, inscribed in the stance of the standing man and the apex of the blue horizon[42]. That dialectic is equally present in Women and Children by the Sea, where the descending diver and the weight of the drowned woman are countered by the mother’s upward energy, as she raises her child high in the air.

The contrast between calm and intensity may be traced further back in Picasso’s work, to his small 1918 Biarritz painting The Bathers (Paris, Musée national Picasso-Paris), which depicts three young women in bathing costumes on a beach. In the foreground, one is recumbent with eyes closed, shaded by a towel, while another, looking away, is plaiting her hair. Behind them, their companion is standing, twisted and agitated, both hands pulling at her hair, her face stretched upwards, as if seeing an imminent threat above the frame of the picture. It may not be a coincidence that in his Biarritz sketchbook, Carnet 214 (private collection), Picasso drew a plane crash, with wreckage and a pilot underwater, on the seabed.

In 1912, fascinated by the Wright brothers, Picasso had adopted Michelin’s upbeat advertising slogan, “Our Future is in the Air” (“Notre Avenir est dans l’air”), including it in three cubist still lives. From the Great War onwards, however, he regularly associated the sky with danger, a change attributable to a letter, dated 1st September 1914, which his mother wrote to him from Spain: “I’m very scared of aircraft because they can sometimes drop a bomb where you are least expecting it”, adding that she prays he will stay safe amidst the troubles of war[43]. The date of the letter is significant, as two days earlier, on 30 August 1914, Paris had been bombed for the first time: a German aircraft had dropped bombs on the 10th arrondissement, near the Canal Saint-Martin[44]. The experience of bombardments in Paris, escalating throughout the war, would reverberate for decades in Picasso’s politics and painting, amplified by subsequent uses of airborne terror, for example over Guernica. In several works from 1918, 1932 and now in 1958, he shifted the depiction of bathers away from habitual associations of well-being and freedom, instead juxtaposing heedless serenity and fearful vulnerability, incorporating danger that plummets from above. At the same time, from Great War to Cold War, Picasso adapted his iconography to the new realities of an atomic age, post-Hiroshima, post-Nagasaki. Painted for UNESCO, his white on black skeletal figure resembles an x-ray (in French “radiographie”): the figure is indeed radioactive, scorched by a fire of solar intensity. Picasso’s “Dove of Peace”, after first appearing on the walls of Paris in 1949, flew blithely round the world, until the artist’s scary new birdman offered a sombre counterpoint.

Over to the left of Picasso’s UNESCO painting, a naked female bather, drawn in comic-book style, rises from the water, looking away from the main event. She contributes to T. J. Clark’s 2016 reading of the work as “tragi-comic”: humour, deflating bombastic and over-reaching ambition, is symptomatic of the huge painting’s place in a post-epic era[45]. Brigitte Léal, for her part, describes this swimmer as “ithyphallic”: she is as phallically male as patently female[46]. She is in fact a relative of the naked, androgynous bathers, whose female anatomy distends into phallic swellings, that Picasso had drawn in two sketchbooks he used during the summer of 1927, in Cannes[47]. If the testicular extremities of the voluptuous bather in the mural may also be perceived as a fishtail, then she is a Mediterranean mermaid, a siren, borrowed from Homer’s Odyssey or Ovid’s Art of Love. Giving her a fishtail (“une queue de poisson”), Picasso activated a relevant French pun on the word “queue”. He also, however, placed an explicit dab of orange paint between her two lower curves, so when that is noticed, they also become buttocks. In that zone of the painting, by creating this playfully erotic, polysemic and gender-bending anatomy, Picasso gleefully subverted the high seriousness conventionally expected of a monumental mural commissioned for a major international institution.

Materials and Technique: a Restorer’s Report

In October 1997, the fine-art restorer Aloys de Becdelièvre provided UNESCO with an illustrated report on work he had recently completed on Picasso’s Conference Building mural[48]. The report describes the condition in which Becdelièvre found the painting, marked by dust, food, building works, cleaning products and graffiti, and explains his restoration procedures. He also reveals, with close-up photographic evidence, some details of the artist’s creative techniques. Returning to the polysemic lower part of the ithyphallic bather, for example, Becdelièvre shows how Picasso first coloured that space with a layer of orange paint, before applying the blue of the sea, so it defined the two curvaceous shapes he wished to retain. To achieve the final skin colour, he next applied two coats of beige onto the retained orange area. Doing this, he carefully left apparent a thin margin of orange, between the blue and the beige, around the edge of the anatomical curves. As Becdelièvre observes, this orange outline creates a subtle, three-dimensional modelling effect: the curves become bulbous. Warming the beige skin-colour, the orange edge also contrasts attractively with the surrounding blue. Picasso “fait chanter le rapport coloré”: he makes the colours sing. Becdelièvre also photographed a small section of the orange line to show how irregular its width and edges are. Against the exacting norms of academic art and fine craftsmanship, Picasso’s speedy brushwork energises the picture.

The restorer’s report also defines the types of paint used by Picasso and how they were applied. Becdelièvre states that for most of the mural, Picasso mixed pigments with water and a binder, such as a casein, to produce a free-flowing paint that easily covered large surfaces and which quickly dried, to allow rapid application of successive layers. Picasso also varied the degree of dilution, so wood-grain is sometimes apparent, while some groups of panels appear less matt than others. Elsewhere, using less diluted paint, his brush left fine, linear ridges, liable to catch any light. Becdelièvre also states that exceptionally, for the black-and-white diver, Picasso used glycerol or oil paint, smooth and fluid, but insoluble in water. The white paint is brilliant, the black is matt. Painting the skeleton, Picasso nevertheless allowed the two oily paints to mingle, so the white bones are darkly discoloured.

Information on materials and techniques identified in the report helps explain how Picasso conferred such charismatic presence on the painting’s macabre central figure. The bones appear to be blackened by fire and smoke, but placed against the matt black halo, the glossy white paint still makes the skeleton stand out in low relief. The difference in surface, colours and forms between the bathers and the diver also accentuates the contrast between softer zones of insouciance and the starkly intrusive central drama. Elsewhere in the mural, brush-strokes are uneven and multi-directional, indicating fast work, as is also apparent in parts of War and Peace. Painting such a large surface, stooping over panels laid on the floor, proved, however, exhausting, so Jacqueline Roque and Picasso’s secretary, Mariano Miguel Montañés, helped him complete the job[49].

“Things I master but don’t fully control”: Interpreting the Painting

Picasso deals in lines, shapes and colours, leaving others to define their meaning. In his UNESCO painting, however, when he depicted his diver as an extraordinary, discoloured skeleton, elongated by velocity and entirely haloed in black, he ensured that the work could not easily be interpreted as just bathers by the sea. In the Vallauris school-yard, after the big reveal, a Radio UNESCO journalist recorded an interview with Picasso, referring to Salles’ speech and asking the artist if he agreed that his painting depicted “l’Icare des ténèbres”. Picasso replied that “a painter paints and doesn’t write” (“un peintre peint et n’écrit pas”), before conceding that “It is more or less what I wanted to say” (“C’est à peu près ce que j’ai voulu dire”). He then added, however, that a long and laborious process had eventually produced a work “expressing things I master, but don’t fully control” (“exprimant des choses dont je suis le maître, mais pas volontairement l’acteur”)[50]. In other words, some half-conscious impulse, or even the work itself, imposes its own imperatives[51]. As Marie-Laure Bernadac put it, “The myth of Icarus, which superimposed itself on the original conception, and which was suggested by Georges Salles, is certainly there in the work, whether consciously or not”[52]. The Icarus connection was strengthened when, in the act of painting, Picasso gave his skeletal figure a round head and thicker bones and joints than in the drawings, operating a gender switch from female to male. Picasso’s occasional alter ego was the Minotaur and he undoubtedly knew the Icarus story well, especially as its primary source is Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which he illustrated in 1931 for the young publisher Albert Skira. In those engravings, he chose, however, to engage with the graphically complex fall of Phaeton and his chariot, rather than the winged boy.

In Vallauris, Jean Cocteau was immediately struck by the huge painting’s tragic aspect. To that same UNESCO interviewer, the poet declared, “We have lived through a tragic era, and we are about to live through another one, and this is either the curtain being lowered on a tragic era or the curtain rising, the curtain of the prologue to another tragic era.” (“Nous avons vécu une époque tragique, nous allons en vivre une autre, et c’est soit le rideau qui se baisse sur une époque tragique, soit le rideau qui se lève, c’est le rideau du prologue d’une autre époque tragique.”) Surveying the painting, Cocteau immediately thinks of a theatre curtain, remembering, no doubt, Picasso’s 1917 curtain for the ballet Parade, based on a Cocteau scenario. The Parade curtain (Paris, Musée national d’art moderne), commissioned by Serguei Diaghilev for the Russian Ballet, measures 1050 x 1640 cm and is the only other Picasso painting comparable in size to the UNESCO mural. In May 1917, Cocteau had watched Picasso add finishing touches to the ballet curtain, laid out on the floor of a film-studio in the Buttes-Chaumont area of eastern Paris, before seeing it again soon afterward, at the ballet’s first performance, at the Théâtre du Châtelet, where the curtain was displayed during Erik Satie’s orchestral Prelude, then raised as the action began[53]. In 1958, as he began another mammoth painting laid out horizontally, Picasso may himself have recalled his Parade curtain, in which the central, background shape of Vesuvius indeed prefigures the central peak of the blue horizon in the UNESCO mural.

At the peak of the Cold War, Cocteau’s reflections on tragedies past and future necessarily imply a reference to atomic bombs and the ongoing threat of nuclear conflict. International tensions would, as he predicted, reach an apogee just four years later, during the Cuban missile crisis[54]. The relevance of Cocteau’s insights is reinforced by Picasso’s description of his own state of mind in the early 1950s when, in Vallauris, he painted Massacres in Korea and War and Peace: “I was like everybody else, obsessed by the threat of war, inhabited by that anguish, and the desire to fight against it” (“j’étais comme tout le monde, obsédé par la menace de la guerre, habité par cette angoisse, et cette envie de se battre contre l’angoisse”)[55]. The act of painting could be cathartic. In Vallauris, Picasso had hoped to see the inauguration of his War and Peace chapel as a French National Museum celebrated at the same time as the unveiling of his UNESCO mural. For him, these works were related.

In 1942, André Breton published in New York “On the Survival of certain myths and on some other myths in growth or formation”, an essay in images which identified fifteen myths that he saw as having retained contemporary vitality and validity. They included, in fourth place, “Icarus”, which Breton illustrated with a detail from Bruegel the Elder’s Fall of Icarus, cut out in the shape of an aircraft propellor, and captioned, “Dusseldorf was bombed yesterday for the fiftieth time (The newspapers)” (“Dusseldorf a été bombardé hier pour la cinquantième fois. (Les journaux)”)[56]. Matisse and Picasso subsequently confirmed the acuity of Breton’s verbo-visual statement. Matisse’s 1943 Fall of Icarus included a blue background lit by yellow flashes which, in its wartime context, suggested exploding shellfire more than stars in the sky. The man in the picture, falling feet-first, his heart red and jagged as a wound, resembles a falling soldier or a pilot dropping through the air. Similarly, Picasso’s momentous wall-painting of 1958 confronted the geopolitical realities of an era permeated by the threat of imminent annihilation.

Once Picasso’s mural was installed in the Conference Building, Le Corbusier wrote to him that he found the painting “superb, it works, it is at one with the era of reinforced concrete” (“superbe, elle tient, elle est de l’époque du béton armé”)[57]. By its scale, palette and schematic layout, the mural does indeed match the spaces, colours and shapes of UNESCO’s concrete interior. The official inauguration of the new buildings would take place on 3 November 1958, in the presence of the President of France, René Coty, and the French Radiophonic Orchestra. That evening, Luther Evans presided a dinner for the UNESCO artists and architects. Well into the evening, responding to a wry remark by Evans, Le Corbusier stood up to declare that, whatever anyone thought, Picasso’s “masterpiece” would be fully appreciated ten or twenty years on. He then got all those present to sign a congratulatory telegram to Picasso, who had stayed in Cannes[58].

Whatever intentions or instincts directed Picasso’s hand when he made his UNESCO mural, we may choose to follow D. H. Lawrence’s advice, “Never trust the artist. Trust the tale.[59]” For a while, UNESCO would label Picasso’s painting The Forces of Life and Spirit Triumphing over Evil. Georges Salles’s “l’Icare des ténèbres” rang truer, however, because of the astonishing charisma of that black and white skeleton, plunging towards the sea. Before long the painting acquired its definitive title, The Fall of Icarus (La Chute d'Icare). Much later, in 1972, one of Picasso’s last works would be his contribution to a facsimile portfolio of his preparatory studies for the UNESCO painting, with a Preface by Jean Leymarie, also published by Skira. A column of words, in Picasso’s handwriting, fills the cover: “Picasso/ La /Chute /de /Icare /Albert Skira”. The consecutive, downward layout of the words visually matches the epic descent they describe and so Picasso validated, in writing, and in extremis, the title his work had acquired. A title shapes interpretation and, as a result, installed near the entrance to UNESCO’s main auditorium, The Fall of Icarus invites delegates and visitors to reflect on possible side-effects of scientific progress and the fatal consequences of unbridled, egocentric ambition.

Once he had accepted “in principle” the UNESCO commission, Picasso fully engaged with the project, but in his own time, imposing his own timetable and his own preferred venue for the unveiling. Even as he accomplished an onerous public commission, Picasso successfully placed an ironic distance between himself and UNESCO’s institutional hierarchy, while staying on good terms with all his personal contacts. The completed painting contradicted all expectations and surprised the artist himself. In many ways unique in Picasso’s output, the painting is also directly related to some of his earlier works and enriched by his creative dialogues with other artists, including Velázquez, Cézanne, and Matisse. As Breton in 1942 and Matisse in 1943 each produced an Icarus associated with aerial bombardment, so Picasso in 1958 created a post-Hiroshima, Cold-War Icarus. The mural’s inherent moral and political relevance, and the grave warning materialised by the macabre figure at its centre, are leavened and complicated, however, by the life-affirming dose of impertinent humour and zestful eroticism which it also administers, and by its affirmation of inalienable creative freedom.

[1] My thanks go to Nuria Sanz, Lynda Frenois, Eng Sengsavang and their colleagues who welcomed me to UNESCO in 2021 and 2023 and provided access to relevant parts of the UNESCO Archives (henceforth UA) and art collection. All translations from French into English throughout this article are by the author.

[2] Minutes of the 11th Session of the Headquarters Committee, dated 18 June 1953. UA, 11 HQ/3.

[3] UNESCO General Conference Extraordinary Session, Supplementary Report of the Headquarters Committee, Paris, 1st July 1953. UA, 2XO/3 Add. 1. 4.

[4] For an architectural study of UNESCO’s Paris headquarters, including sections on two rejected projects and commissioned art and artists, see Christopher E. M. Pearson, Designing UNESCO: Art, Architecture and International Politics at Mid-Century, London and New York, Routledge, 2010.

[5] In a letter dated 26 September 1956 to his “dear friend” George Salles, Picasso gifted his War and Peace to the French State. See Johanne Lindskog, “La Chute d’Icare, une œuvre vallaurienne ?”, in Picasso Les années Vallauris, ed. Anne Dopffer and Johanne Lindskog, Paris, RMN, 2018, pp. 106-110 (p. 109). My thanks to Anne-François Gavanon for this document. Picasso drew four affectionate portraits of Salles, dated 1st April 1953. Salles would eventually leave the drawings and important Picasso paintings to the French Museum of Modern Art.

[6] CCA meeting 16-18 May 1955, minutes dated 31 May 1955. UA, 1 CCA/8. Miró was awarded an alternative commission (two mosaics). Léger died in August 1955.

[7] Archives Picasso, quoted in Brigitte Léal, Musée Picasso Carnets Catalogue des dessins, vol. 2, Paris, RMN, 1996, p. 271, note 3. With the letter, Salles included plans of the building.

[8] Second CCA meeting, 3-4 November 1955. Minutes dated 20 September 1956. UA, 2 CCA/5.

[9] Minutes of the Headquarters Committee meeting, 17 January 1957. UA, 9 CCA D/Y.

[10] Louise S. Robbins, "The Library of Congress and Federal Loyalty Programs, 1947-1956: No ‘Communists or Cocksuckers’". The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, vol. 64, no. 4, October 1994, pp. 365-385.

[11] Jens Boel, “An American Paradox: Liberal Ideas and McCarthyism at UNESCO”, American Historical Association Annual Meeting, Chicago, 3 January 2019 (https://aha.confex.com/aha/2019/webprogram/Session18117.html ) Boel was Chief Archivist at UNESCO.

[12] Picasso’s politics did not prevent him from meeting former President Harry S. Truman during his 1958 European tour. Photos show Picasso, smartly dressed, shaking hands with Truman as he welcomes him to the Madoura pottery workshop in Vallauris, 11 June 1958, and then, later the same day, him and Jacqueline with Truman and his wife on the terrace of Château Grimaldi in Antibes. https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/photograph-records/2009-1933 and https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/photograph-records/2009-1934.

[13] The architectural maquette and the date it entered Picasso’s possession are cited in Minutes of CAA meeting, 21-22 octobre 1957. UA, 4 CCA/4.

[14] Minutes of CAA meeting, 1-3 Oct 1956. UA, 3 CCA/10.

[15] Minutes of Headquarters Committee meeting, 16 January 1957. UA, 9/16.1.1957 CCA.

[16] Note from the President of the CCA, dated 12 August 1957, addressed to CCA members, in advance of their next meeting. UA, 4 CCA/3.

[17] Minute of CAA meeting, 14 March 1957. UA, CCA/WG 2.

[18] Roland Penrose, Picasso His Life and Work, Revised Edition, New York, Icon, 1973, p. 427.

[19] See Annie Cohen-Solal, Un étranger nommée Picasso, Paris, Fayard, 2021, pp. 400, 433-34.

[20] John Richardson, with the collaboration of Marilyn Mc Cully, A Life of Picasso The Triumphant Years 1917-1932, New York, Knopf, 2007, pp. 354-56.

[21] Henri Laugier, hand-written letter, without envelope, Antibes, 26 September 1957. UA, D4.

[22] Letter dated 30 September 1957, from Zehrfuss in Paris to Erena in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat. UA, BNZ/1613.

[23] Contract-letter dated 24 October 1957, from Jean Thomas to Picasso, agreed and signed by Picasso. UA, HQ/703 382.

[24] Hernán Vieco, “Report on a fact-finding visit to Picasso” (“Oeuvre de Monsieur P. Picasso Compte rendu d’une mission d’information auprès de Picasso”). UA, D4.

[25] Zervos XVII, 409. See Gaëton Picon, Pablo Picasso “La Chute d’Icare” au Palais de l’UNESCO, Genève, Skira, “Les sentiers de la creation”, 1971, pp. 10-11.

[26] Brigitte Léal, “Les Carnets de l’UNESCO”, Musée Picasso Carnets, vol. 2, op. cit., pp. 269-80 (p. 269).

[27] Private collection. Gaëton Picon, op. cit., pp. 108-09. Zervos XVII, 39.

[28] Picasso may also have seen Jazz, Matisse’s illustrated book of 1947, which includes a different version of his Fall of Icarus (Plate 8), accompanied by the artist’s text “L’Avion” (“The Aircraft”).

[29] Gaëton Picon, op. cit., pp. 108-09.

[30] Letter dated 24 March 1958, from Pierre Marcel in Paris to Erena in Nice. The letter also requested any technical information that would facilitate installation of the panels at the UNESCO headquarters. UA, BNZ/1921.

[31] Madeleine Riffaut, “Hier après-midi à Vallauris La fresque géante de Picasso a été dévoilée”, L’Humanité, 30 March 1958, p. 2.

[32] For photos and film-stills, see John Richardson, Picasso and the Camera, New York, Gagosian Gallery, 2014, pp. 343-45.

[33] Anon., “Picasso art for U.N. is shown first time”, The New York Times, 28 March 1958, p. 21. See also, Anon., “Art: Skeleton for UNESCO”, Time, vol. LXXI, no 15, 14 April 1958.

[34] Salles quoted by Madeleine Riffaut, “Hier après-midi à Vallauris”, op. cit., A version of Salles’ speech would later be published: “Une œuvre significative de l’art contemporain”, Chronique de l’UNESCO, vol. IV, no 10, October 1958, pp. 290-292.

[35] Pierre Cabanne, Le Siècle de Picasso, vol. 4, La Gloire et la Solitude, Paris, Denoël, 1975, p. 56.

[36] Bernard Zehrfuss, “L’Histoire d’un palais”, in L’UNESCO. Foyer vivant des bonheurs possibles, Paris, UNESCO/Flammarion, 1991, cited by Pearson, op. cit., p. 296.

[37] Anon., “Paulo Picasso a remis à l’UNESCO la fresque de son père”, L’Humanité, 7 avril 1958, p. 2.

[38] Letter from Jacques Jaujard, Director General of “Arts et Lettres” at the Ministry of National Education, Youth and Sports, granting permission for storage, as requested in a letter of 25 April 1958. UA, HQ/758.581.

[39] Letter from J. P. Ulrik, Secretary of the CCA, to Jacques Jaujard, copy to Breuer, Nervi and Zehrfuss. The panels were to be installed by the contractor Marc Simon. UA, HQ758.761.

[40] Brassaï, Conversations avec Picasso, Paris, Gallimard, 1964, pp. 92-93. Picasso’s diver also resembles some aboriginal paintings. In Arnhem Land, Northern Territory of Australia, rock spirits known as Mimi are sometimes depicted with round heads, always with thin, white, elongated limbs. My thanks to Elizabeth Cowling for this suggestion.

[41] Picasso, Femmes et enfants au bord de la mer, Zervos VIII, 63. See Serge Linares, in UNESCO Art Collection, Selected Works, conception and coordination Nuria Sanz, Paris, UNESCO, 2021, pp. 198-99. Under the heading “Equity. The Fall of Icarus, Pablo Picasso”, the UNESCO catalogue includes three articles on Picasso’s mural, by Juan José La Huerta Alsina, Serge Linares, and Peter Read. The catalogue is available in English and French, in print and online open access.

[42] Linares, op.cit., p. 199.

[43] See Annie Cohen-Solal, Un Étranger nommée Picasso, op. cit., p. 271.

[44] Anon., “Un aéroplane allemand lance trois bombes sur Paris”, L’Excelsior, 31 August 1914, p. 2.

[45] T. J. Clark, “Picasso and the Fall of Europe”, The London Review of Books, vol. 38, no. 11, 2 June 2016, pp. 7-10.

[46] Brigitte Léal, “Les Carnets de l’UNESCO”, op. cit., p. 269.

[47] Sketchbooks 015, MP 1874 and 011, MP 1990-107. See Brigitte Léal, Musée Picasso Carnets, op. cit., pp. 81-95. Later in 1927, back in Paris, Picasso proposed these drawings as ideas for a monument to Apollinaire, another rare commission he had accepted. Apart from the UNESCO mural, Picasso’s only other commissioned public artwork in Paris is his bronze Head of Dora Maar, given by the artist as a monument to Apollinaire, in Laurent Prache Square, Saint-Germain-des Prés, inaugurated on 5 June 1959, and already on the artist’s mind in 1958. See Peter Read, Picasso and Apollinaire The Persistence of Memory, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, University of California Press, 2008.

[48] Aloys de Becdelièvre. À UNESCO Paris. Rapport de restauration. Lyon, le 1er octobre 1997. UA.

[49] Pierre Cabanne, Le Siècle de Picasso, vol. 4, op. cit., p. 55.

[50] Recording accessible at https://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/document-5535

[51] Picasso later wrote, “Painting is stronger than me it makes me do what it wants” (“La peinture est plus forte que moi elle me fait faire ce qu’elle veut”). Carnet 56, inside back cover, dated 27 March 1963, in Brigitte Léal, “Les Carnets de l’UNESCO”, op. cit., p. 300.

[52] Marie-Laure Bernadac, “Picasso 1953-1972: Painting as Model”, in Late Picasso, London, The Tate Gallery, 1988, pp. 49-94 (p. 69).

[53] See Parade, ed. Claire Garnier, Metz, Centre Pompidou-Metz, 2013; Peter Read, “Cubism Breaks Cover: Picasso and Parade in 1917”, The Cubism Seminars, ed. Harry Cooper, Washington D.C., National Gallery of Art, 2017, pp. 252-85.

[54] Cocteau would confide in his journal that he found the UNESCO painting “hideous and empty” (“hideuse et vide”), again comparing it to a curtain lowered or raised on past or future tragedies. Jean Cocteau, Le Passé défini Journal, vol. VI, Paris, Gallimard, 2011, pp. 93, 95.

[55] Picasso quoted in Claude Roy, L’amour de la peinture (revised edition), Paris, Gallimard, 1987, p. 235.

[56] André Breton, Œuvres complètes, III, ed. Marguerite Bonnet and Étienne-Alain Hubert, Paris, Gallimard, “Bibliothèque de la Pléiade”, 1999, pp. 127-42 (p. 131).

[57] Le Corbusier, letter to Picasso, 23 octobre 1958, in Picasso Méditerranée, ed. Émilie Bouvard, Camille Frasca, Cécile Godefroy, Paris, Musée Picasso-Paris / In Fine, 2020, p. 304.

[58] Brassaï, op. cit., p. 321.

[59] D. H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature, NY, Thomas Seltzer, 1923, chapter 1.

Fig. 1

Pablo Picasso

La Chute d'Icare, 1958

Acrylique et peinture à l'huile sur panneaux de bois, 910 X 1060 cm

UNESCO

Fig. 2

Pablo Picasso

Atelier, étude pour la peinture murale de l’UNESCO, Cannes, 6 décembre 1957

Crayon bleu, crayon graphite, encre noire et gouache sur papier

50,5 x 65,5 cm

Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, Madrid

Fig. 3

Pablo Picasso

Étude pour « Les Baigneurs » : le tremplin, Cannes, 8 Septembre 1956

Encre et crayon graphite sur papier, 20,8 x 26,8 cm

Musée national Picasso-Paris

Dation Pablo Picasso, 1979

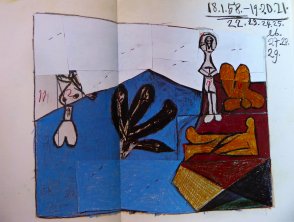

Fig. 4

Pablo Picasso

Carnet de dessins pour l'Unesco, Cannes, 15 décembre 1957 - 4 janvier 1958

Crayon de couleur et encre sur papier imprimé, 32 x 24 x 1 cm

Musée national Picasso-Paris

Dation Pablo Picasso, 1979

Fig. 5

Pablo Picasso

L'Atelier : la femme couchée, le tableau et le peintre, Cannes, 4 Janvier 1958

Crayon graphite sur papier, 50,5 x 65,5 cm

Musée national Picaso-Paris

Dation Pablo Picasso, 1979

|

Fig. 6

Pablo Picasso

La chute d’Icare, étude pour la peinture murale de l’UNESCO, Cannes, 18-29 janvier 1958

Fusain, crayon bleu et craies grasses de couleur sur papier

50,7 x 65,8 cm

Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, Madrid

Visuel publié dans : Gaëtan Picon, « La Chute d’Icare » de Pablo Picasso, Genève, André Skira, « Les Sentiers de la Création », 1971, pp. 108-109.

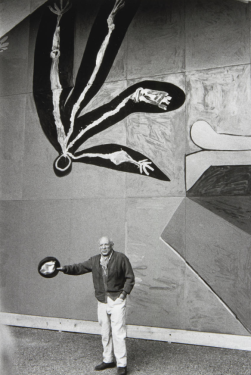

Fig. 7

Inge Morath

Pablo Picasso lors du dévoilement de « La Chute d'Icare », Vallauris, mars 1958.

Fig. 8

Edward Quinn

Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau et Maurice Thorez lors du dévoilement de « La Chute d'Icare », Vallauris, mars 1958