Painting for the age of béton armé : "La Chute d’Icare" and its creative process

This text was part of a public communication on current research at the Musée national Picasso-Paris, given during the international symposium "Célébration Picasso" that took place on the 7th and 8th of December, 2023, at UNESCO.

In conversation with the photographer Brassaï in October 1962, the dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler voiced some shared beliefs regarding Pablo Picasso’s artistic practice. Kahnweiler explained how the artist did not like “commissions very much. Guernica. War and Peace, he created them spontaneously. And he agreed to do the Unesco panel somewhat reluctantly, giving in only at Georges Salles’s insistence. But really, he was not rewarded for his effort. None of his other works were so poorly received.”[1] For its important location at the core of UNESCO House in Paris, the mural-size painting Picasso realized for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization in 1957-58, identified by Kahnweiler simply as “the Unesco Panel”, has aroused polarized reactions since its inauguration. Commentators struggled to understand the painting’s haphazard look, featuring basic shapes, faltering lines, and rough brushstrokes, and questioned whether Picasso had approached the commission with earnestness. Equally undermining its thematic relevance, the literary title of La Chute d’Icare, by which it is known, has come to be seen as a gimmick Salles, an old friend of Picasso, scholar of Asian art, and, by 1958, head of the Musées de France, came up with when the mural was inaugurated to crystallize the meaning of the work. Tracing its origins and realization through some of its preparatory drawings, this essay aims to shed new light on the relationship with its brutalist architectural setting, seen as a productive dialogue rather than a failed integration.

After the final plan for UNESCO House was agreed upon in February 1953, the issue of the works of art that would complete the building became increasingly urgent and a Committee of Art Advisers (CAA) was appointed in March 1954 to oversee the selection of these artworks.[2] As the CAA started to meet in May 1955, it became immediately clear that the lobby of the General Conference Building, where the architects had envisioned a large mural work, was a particularly prominent site. An internal debate ensued between Georges Salles, who suggested Picasso, together with Fernand Léger and Joan Miró, and the British art historian and critic Herbert Read, who proposed a roster of younger artists.[3] While Salles was able to overcome Read’s skepticism, the other committee members, including the architects who were present (namely Marcel Breuer, Sven Markelius, Ernesto Rogers, and Bernard Zehrfuss), insisted on the central role the building should play in every commission. By the CAA’s second meeting of early November 1955, Salles had already secured tentative agreements from the majority of the artists chosen for the main projects, including Picasso. “No special theme would be suggested to the artists,” a report stated, “but the architects would explain UNESCO’s aims to them and give them a copy of the Constitution of UNESCO.”[4]

When the art advisers reconvened in Paris in October 1956 to discuss the progress of the different projects, Zehrfuss, serving as the overall project manager, had already been tasked with the challenging responsibility of coordinating with Picasso. As we learn from a subsequent report, “Salles and Zehrfuss paid a visit to Mr. Picasso over the summer and saw exhibited in Vallauris his ceramic works with mythological figures which can be considered as a preliminary project for the decoration of the wall of the Conference building. Mr. Picasso declared that he could not execute a special maquette as his inspiration for the final project would not consider any of his previous sketches. The Committee, therefore, recommended that a letter be sent to the artist by the President, accepting the principle of a ceramic decoration.”[5] Picasso could have initially conceived his mural for UNESCO as a set of ceramic panels which would have been realized in all likelihood in Georges and Suzanne Ramié’s Atelier Madoura.[6] “In his studio”, Zehrfuss recalled, “he operated in front of me a dazzling demonstration of the project with various materials and wanted to create a work in white and black tones.”[7]

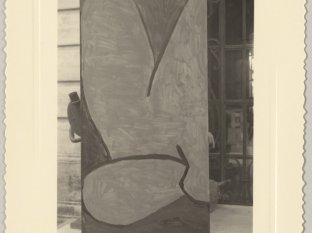

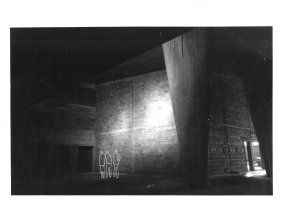

As communications between UNESCO officials and Picasso lagged, a letter demanding a formal response from the artist was eventually sent by the CAA and photographs of the wall entrusted to Picasso shared via Georges Salles.[8] These photos, copies of which still survive in the UNESCO archives (fig. 1), demonstrate that, despite never visiting the construction site (or even the finished building, it seems), Picasso was made aware of the space allotted to him early on, its privileged viewpoints, and the difficulties entailed by the modernist architecture, particularly the presence of a large concrete walkway providing access to the projection room of the assembly chamber. Another official document confirms that the artist was “in possession of a model of the Conference building since June 1956.”[9] Architectural plans of UNESCO House (fig. 2) might also have been supplied to the artist. This awareness of the architectural environment prompts us to reconsider a prevailing view regarding the mural’s difficulties and subsequent setbacks, suggesting they were not merely unintended consequences of its placement. “The architects offered him a very large surface,” Brassaï explained expressing this stance, “but you can’t see it from a suitable distance. That’s what’s shocking. As soon as you step back, a catwalk cuts off the panel."[10]

In the following months, Salles kept playing a key role in ensuring Picasso’s continued involvement. By March 1957, a report confirms, “the artist abandoned the idea of a ceramic decoration in favor of a mural painting in oil. This would be made in his atelier on isorel panels. […] The architects agreed to write to Picasso to coordinate with him regarding the issues of format, numbering and the installation of the panels, whose joints require special care.”[11] The immediate precedent for this approach were the two large-scale paintings La Guerre et la Paix for the Romanesque chapel of Vallauris, each executed on eighteen isorel panels assembled together on a scaffolding after being painted in Picasso’s Vallauris atelier, integrated by Les Quatre parties du monde, added on the end wall while the artist was working on the UNESCO commission. If their scale had allowed the artist to work on the overall composition as if on a traditional painterly surface, it quickly became clear that this would not be possible in the case of UNESCO, where a much bigger architectural scaffolding would be needed to assemble the finished panels. Even with these challenges, as it is confirmed by Roland Penrose, who often visited villa “La Californie” while writing his biography of the artist, Picasso was determined to undertake the project himself, despite acknowledging that he was “no longer 25”.[12]

Penrose’s recollections are generally reliable. Nonetheless, in his biography, he inaccurately asserts that it was not until the spring of 1958 that Picasso found “his own solution”. Seeing that it was impossible for him to complete the whole mural in one piece he decided to divide it into panels small enough to be placed on the floor of his studio in groups of some dozen at a time.”[13] Archival evidence shows that this solution was found, in fact, at the end of September 1957, following a personal meeting between Picasso and Henri Laugier, a respected physiologist, UNESCO board member and partner of Marie Cuttoli. Picasso basically accepted that the surface he would have to paint would be designed by someone else. The role of the UNESCO architectural team in conceiving the complex system of forty panels to be installed in a meticulously studied way, documented by several technical drawings, cannot be underestimated.[14] As Zehrfuss made clear, “the difficulty lies in the method of fixing the plywood panels. We need to find a system that can be disassembled (for transportation) and reassembled easily, and these fixings should not be visible.”[15]

When on 28 October 1957 a UNESCO delegate was sent to Cannes to convince Picasso to finally sign his contract, he reported that “Mr. Picasso in agreement with Mr. Erena and Rapastelli, has decided to carry out his work in his villa and no longer use the hall of the Hôtel Martinez.”[16] The artist’s initial decision to rent the huge Salle des Fêtes of the Hôtel Martinez in Cannes, then closed to customers, was likely an attempt to find a set-up which would allow him to work on the whole painterly surface at any time, as Picasso was still reflecting on the “difference between the methods of the fresco painter and his own” he described to Penrose.[17] The artist had to come to terms quickly with this issue as he started sketching out his ideas from 6 December. A grid squaring up the composition features prominently in the studies from 15 December, testing how the edge of each panel would coincide with the figures or intersect them.[18] This grid thus influenced the overall arrangement of the elements devised by the artist.

Picasso’s preliminary solutions for the mural, conceived while he was still completing the cycle of canvases inspired by Velázquez’s Las Meninas, were set indoors. His confrontation with the great masters of the past such as Velázquez, absorbing and transforming their legacy, bespeaks the challenge of defining his own place in history, a challenge that he certainly felt in the case of the monumental official commission he had received from UNESCO. He thus resorted to the favored theme of a model reclining in an artist’s atelier, the space of artistic creation itself and a comfort zone – a place that had also been his point of departure for Guernica. The world of the beach, which eventually came to dominate the UNESCO painting, was present from the very beginning, but through a mise en abyme. Indeed, in the middle of the space stands a canvas on an easel, easily identifiable as Baigneurs à la Garoupe (1957, MAH, Musée d’art et d’histoire, ville de Genève), filled with totem-like bathers. These figures are mediated in multiple ways: they are painted (or drawn) equivalents of Picasso’s first (and only) sculptural ensemble, composed of pieces of salvaged wood in 1956 (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart), and subsequently cast in bronze.[19] Picasso himself explained to Pierre Daix how there was a real debate between painting and sculpture.[20] The artist, still present on the right-hand side of the composition, advances and retreats throughout the series, while the easel painting of the bathers becomes square in format.

On 7 January 1958 Picasso completed a series of lavish color studies, further simplifying the composition to play off the curvilinear forms of the female nude of the model on the left against the rectangular bathers. The last two studies of that day show the full shadow of the artist looming large and replacing the only bather left on the canvas, the diver. “It went on for months and months, and little by little it was transformed without me even knowing where I was going, do you follow?”, Picasso succinctly explained to the journalists interviewing him at the mural’s unveiling in Vallauris in March. “It began in a studio where there were pictures, it was my studio where I was in the process of painting, do you understand? – And little by little the picture ate up the studio, there was nothing left but the picture, which said – which expressed – things I was master of but not acting of my own free will.”[21]

Indeed, around mid-January Picasso got rid of the entire motif of the painter’s studio that he had been elaborating for over a month. The final maquette, which Picasso worked on from January 18 to 29, featured a radically new outdoor scene with bathers on the shore and introduced a new working method. The new composition was gradually put together on a large, roughly gridded sheet onto which Picasso then began to pin various rectangular bits of paper with figures and other compositional elements. In doing so he was reviving a method he had first employed in early cubist works to explore compositional ideas. Picasso proceeded this way through the rest of the month, successively inscribing the passing days on the upper right corner of the sheet. Ultimately, the cast of characters was narrowed down to five. At the heart of the final composition emerged a falling stick figure comprising four limbs and an empty head, its body delineated in white against a dense black halo. None of the preparatory drawings supports the idea that Picasso had the myth of Icarus in mind during the execution of the commission for UNESCO. This reading, therefore, remains unlikely and seems to offer a layer of meaning which was added only retrospectively by Georges Salles.

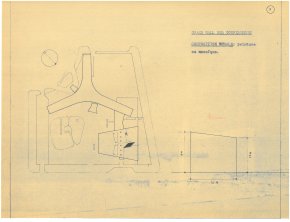

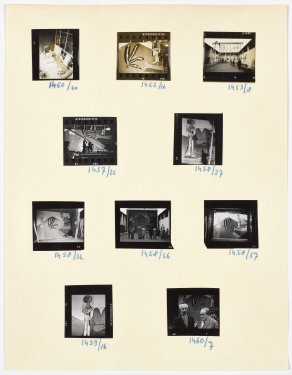

One of the rare photographs documenting the work-in-progress taken by Jacqueline Roque (fig. 3) shows some of the panels set upright in the background, supported by a wooden framework, to be observed as a unified whole, while in the foreground Picasso is painting an individual panel, held up between two chairs and positioned horizontally. Picasso’s work on the mural took place in a dynamic tension between horizontal and vertical, between individual and combined panels, between fragments and larger sections of the composition, while the total view remained unattainable. Structural and design considerations played an important role in determining the composition, confirming that it did not come as spontaneously as Kahnweiler would suggest regarding La Guerre et la Paix. In the courtyard of the Anfosso school in Vallauris, where the mural was inaugurated for the general public on 29 March 1958 and officially presented to UNESCO officials on 5 April, a proper stage had to be built, including a scaffolding of adequate size to allow the panels to be fixed. Photographs of the assembly process (fig. 4) show how the effective shape and size of the pictorial field was only gradually revealed and to what extent the structure designed by the UNESCO architects in agreement with Picasso ultimately guaranteed the unity of the composition.

A thorough discussion of the criticism the UNESCO painting received after it was at last installed to the lobby wall of UNESCO General Conference Building on 20-23 August and officially in October 1958 is beyond the scope of this essay. Two of the few dissenting voices, however, and perhaps not coincidentally, highlighted the productive interaction between the architecture and the mural. In a succinct note of endorsement, Le Corbusier wrote to Picasso that his painting was “ superb, it holds together, it belongs to the age of béton armé.”[22] While describing the building as “this dated dream of Gesamtkunstwerk”, the architectural critic Reyner Bahnam praised only Picasso’s mural among all the artworks as “visually and functionally related to the building.” As Banham noted, “the bridge is put to work, as a mask that reveals successive layers of the composition as one approaches from the pas-perdus, and as a vantage point for high level views of the busier areas of the iconography.”[23] In conclusion, rather than being a “picture without a viewpoint”, as argued recently by T.J. Clark,[24] a more careful consideration of its site-specificity allows to look at La Chute d’Icare and its creative process differently.

Research for this essay was made possible with the generous support of FABA – Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso as part of its Research Program (2021-24). https://www.fabarte.org/en/projects/20-research

An extended version of this essay will appear in the forthcoming catalogue of the Museo Picasso Malaga, which from 19 March 2024 to 21 March 2027, proposes a new presentation of its Collection curated by Michael FitzGerald, in collaboration with FABA. https://www.museopicassomalaga.org/en/exposiciones/pablo-picasso-structures-of-invention

[2] For more information on the CCA, see Christopher E.M. Pearson, Designing UNESCO: art, architecture and international politics at mid-century, Farnham, Ashgate, 2010, pp. 223-254.

[3] UNESCO Archives. 1 CCA/SR.4. “Première session. Procès-verbal provisoire de la quatrième séance” of 17 May 1955. Report in French dated 20 May 1955.

[4] UNESCO Archives. 2 CCA/5. CCA Second Meeting (3-4 November 1955). Report in English dated 28 November 1955.

[5] UNESCO Archives. 3 CCA/10. CCA Third Meeting (1-3 October 1956). Report in English dated 22 October 1956.

[6] Furthermore, as reconstructed by Johanne Lindskog, in July 1957 the mayor of Vallauris, Paul Derigon, proposed to Picasso to realize preparatory drawings for the facade of a large Palais des Expositions that he envisioned to be made of ceramics. See Johanne Lindskog, “La Chute d’Icare, une œuvre vallaurienne?”, in Picasso: les années Vallauris, eds. Anne Dopffer and Johanne Lindskog, Paris 2018, pp. 106-110.

[7] Bernhard Zehrfuss, “L’histoire d’un palais,” in L’UNESCO. Foyer vivant des bonheurs possible, Paris, UNESCO/Flammarion, 1991, pp. 8-17, in particular footnote 4.

[8] UNESCO Archives. X07.354.11. Letter from Michel Dard, Chef de la Division des Échanges culturels internationaux, to Georges Salles: “Je joins également trois photographies du mur confié à Picasso, que vous pourrez lui faire parvenir.”

[9] UNESCO Archives. 4 CCA/3. Note by the Chairman in preparation for the CCA Fourth Session (21-22 October 1957). Report in English dated 12 August 1957.

[10] Brassaï, Conversations, op. cit., p. 357.

[11] UNESCO Archives. CCA/WG2. CCA Second Working Group (14 March 1957). Report in French dated 19 March 1957.

[12] See Elizabeth Cowling, Visiting Picasso: the notebooks and letters of Roland Penrose, London, Thames & Hudson, 2006, pp. 200-201.

[13] Roland Penrose, Picasso: his life and work, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1971, p. 427.

[14] UNESCO Archives. HQ/101. “Picasso” folder. A handwritten document on UNESCO letterhead, presumably by Zehrfuss, contains a schematic drawing outlining the structure of Picasso’s mural, complete with dimensions and instructions for assembly.

[15] UNESCO Archives. HQ/101. “Picasso” folder. Letter from Zehrfuss to Erena, 16 October 1957.

[16] UNESCO Archives. HQ/101. “Picasso” folder. “Compte-rendu d’une mission d'information auprès de M. Picasso.”

[17] Penrose, Picasso, 427: “the Renaissance artists painted a small area on a newly prepared surface every day and knew from their sketches where the joins were to come, but he himself liked to extend his painting at any time over the whole surface and without restriction, working either on details or on the overall effect as he felt inclined.”

[18] The preparatory drawings for the mural have been published in Gaëtan Picon, “La Chute d’Icare” de Pablo Picasso, Genève, Albert Skira, 1971. For the grid, see the study reproduced on p. 28.

[19] On the importance of the group of Bathers in the conception of the UNESCO composition, see Émilia Philippot, “Sur le sentier des Baigneurs à La Chute d’lcare,” in Picasso: baigneuses et baigneurs, eds. Émilie Bouvard and Sylvie Ramond, Gand, Snoeck, 2020, pp. 67-73.

[20] Pierre Daix, Picasso, Paris, Hachette Pluriel Editions, 2014, p. 493.

[21] Picasso’s interview with a journalist of Radio UNESCO is easily accessible online <https://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/document-5535>.

[22] Letter from Le Corbusier to Picasso, 23 October 1958. Published in Les Archives de Picasso: “on est ce que l'on garde!”, Paris, RMN, 2003, p. 122. For Le Corbusier’s positive reaction, see also Brassaï, Conversations, p. 358.

[23] Reyner Banham, “Unesco House”, in Reyner Banham, A Critic Writes: Selected Essays by Reyner Banham, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1996, pp. 30-31.

[24] See T.J. Clark, Heaven on Earth: painting and the life to come, London, Thames and Hudson, 2018, p. 220.

Fig. 1

Photograph of the construction site and the space allotted to Picasso

UNESCO Archives, box HQ/129

Fig. 2

Architectural plan of UNESCO House highlighting “The Picasso Wall”

UNESCO Archives, box CCA/1, 1 CCA/6

Fig. 3

Jacqueline Roque

Picasso working on the panels forming the UNESCO mural.

Published in: Picasso: la pièce à musique de Mougins (Paris, Centre culturel du Marais-Jacqueline et Maurice Guillaud, 1982), p. 188.

Fig. 4

Inge Morath

Photo album page with shots by of the installation of the UNESCO mural in Vallauris for its inauguration, 28 March 1958.

UNESCO Archives, Photo Album M3.

Plus de contenus sur "La Chute d'Icare"

- Photographiess.d.APPH1695

- Photographiess.d.MP1987-36

- Photographiess.d.APPH6026

- Photographiess.d.APPH14596

- Photographiess.d.APPH14597

- Photographiess.d.APPH14601

- Photographiess.d.APPH14605

- Photographiess.d.APPH1678