Alone, in Front of the Mirror. Absences in Picasso’s Studio

This text was part of a public communication on current research at the Musée national Picasso-Paris, given during the international symposium "Célébration Picasso" that took place on the 7th and 8th of December, 2023, at UNESCO.

The distinction, as immediate judgement, of individuality as being for itself from itself as merely being, is the awakening of the soul, which initially confronts its self-enclosed natural life, as a natural determination and a state, with [another] state, sleep.

– G. W. F. Hegel[1]

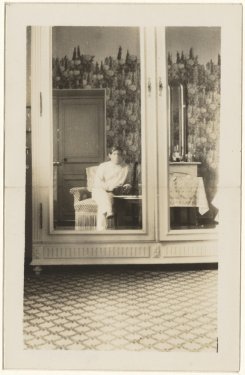

In Brassaï’s Conversations, Picasso declared to his friend that photography had liberated painting from the subject. “In any case,” the artist continued, “a certain aspect of the subject belongs henceforth to the domain of photography.”[2] In a self-portrait from 1921 (APPH2797), it is the subject that now becomes the pretext for the optical trap into which Picasso draws the spectator (fig. 1). We encounter the artist alone, in an elegant interior. Elegant himself, Picasso manipulates his camera, turning it towards the mirrored wardrobe, which occupies the entire upper half of the image. A scene of introspection… And yet, this uninterrupted dialogue between what is in front of the mirror for the photographer, and in front of the photograph for the spectator, involves the latter in an addictive game of illusion, where the continuous reciprocity of the gaze between the artist and us is merely an effect of reflection. Picasso also captured a door in this photograph. But is it still possible to escape this visual trap? Or is it too late to recognise whether it is the artist or us, shimmering on the surface of the mirror in the depth of the room?

The obstinacy wherewith Picasso reveals himself in the role of the author in this shot manifests a profound desire of the artist to challenge the limits of the representational power of the medium. In this photograph with a mirror, we no longer know who is who in the act of looking. While Rosalind Krauss considers the act of photographic recording as a moment of the reflection of reality,[3] Picasso puts a mirror in front of us. The negation of the medium reveals itself in the framing chosen by the artist, since the photograph, as if taken in the seizure of a scopic pulsion, does not primarily reflect reality but unveils the agent of the photographic act, thus interrupting the conventional boundary between the medium and ourselves.

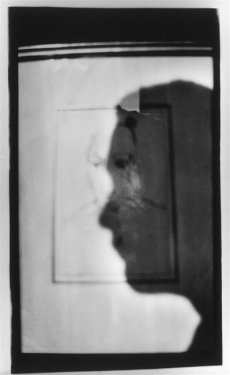

In another photograph, taken in 1927,[4] Picasso projects himself, probably, onto one of his framed figure studies hanging on the wall of his studio (fig. 2). The artist developed two prints of it: the second one, from the same negative, less blurred this time, offers a better contrast between light and shadow. The precise identification of the drawing was inconclusive. It is probably one of the studies of the female figure originally intended for Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.[5] The identification of the individual casting his shadow onto the sketch is just as difficult.[6] Unlike his previous attempts at photographic self-portraiture, this time Picasso does not show himself to the spectator. He substitutes himself with his own shadow, a profile in black superimposed on a head sketched in pencil. Light against shadow. Positive against negative. Reality against imaginary… The interaction between the world of the real and the world of the imagined is captured by the painter in a decisive moment for the constitution of the artist as another element in the photographic composition. For the painter's shadow does not just penetrate the surface of the drawing. It also invades the face of the figure already inscribed within it. As Anne Baldassari stated in her analysis of the photography, “the painter is in the painting, is the painting. It is no longer a question of representation, or even presentation, but of action.”[7] This illusion en abîme seems to overcome the desire to be recognised because, probably, Picasso's objective in this so-called self-portrait is another…

Being an in-dividual[8]

Between six and eighteen months old, as Jacques Lacan explained in his studies on subjectivity, the child undergoes an experience that will change its relationship to itself forever: it becomes conscious of its corporeality in the reflection of the mirror. Lacan characterises the mirror stage as “[...] an identification in the full sense that analysis gives to this term: namely, the transformation produced in the subject when it assumes an image.”[9] For the psychiatrist, the moment of recognition in the mirror reflection thus initiates an irrevocable process of transformation in the child. Until then, it had no idea of its physical integrality. Its limbs did not seem its own. Faced with its physicality reflected in the glass, the child starts now to constitute itself as a subject. Lacan considers this act to be a “primordial identification,” because in the mirror stage, the child does not identify itself in the reflection as an I in the linguistic sense of the word.[10] The identification in the mirror provokes in the subject the development of an “ideal-I” which – unlike the linguistic I – is unique and singular for each individual.[11] Henceforth, the “ego” that was in discordance with reality is situated by the “I” in the fictive axis,[12] developing in the child a particular awareness of the external world, “from the Innenwelt to the Umwelt.”[13] In this constant dialogue between the I in front of the mirror and the I in the mirror, between the I of here and the I of there, the subject acquires an undeniable conviction of its physical wholeness. Its body, which until now had been fragmented in its conception, now becomes a unity. The role of this stage in the construction of identity is all the more relevant since the subject – in its reflection in the mirror – conceives itself as an image. It recognises itself as the same, and it is only through the integration of that visual appearance with that of its own body that the subject perceives itself as a whole.

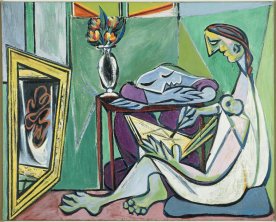

As enigmatic as the origin and motivation for the creation of the photograph with a shadow may be, Picasso gives us some insights about the circumstances of its execution by inviting the spectator directly into his atelier. In a studio scene, painted between 1928 and 1929, we witness an act of creation (fig. 3). The silhouette of the painter, projected onto the studio wall on the right, looks after his work of art, placed on a table. The identification of the figure on the left of the table is, nevertheless, far from evident. Reduced to a few lines, it seems to be the only person acting in the studio. Its right arm leads us to the sculpture set on the furniture, while its left hand is tracing the shadow of the profile on the wall. The constellation of gestures and relationships between the components of the studio allows one to identify the figure as that of the painter himself. He is creating by drawing himself. Or is it the other way round? The figure of the painter is standing in front of a mirror in which reflection,[14] both arms of the artist can be seen. The dialectic between the painter, his reflection and his projection, linked together by the artist's excessively long arms, makes of the space of the studio a place of identification through creation. We capture the painter immersed in his reflection at the moment of the deepest assumption of his self, an assumption as image, which the painter anticipates by tracing the contour of his reflection.[15]

The same procedure is clearly visible in a reprise of this subject from the same year. Peintre et son modèle demonstrates how the act of creation can become for the painter an act of identification. In the studio, whose composition en bloc seems to be the expression of what Carl Einstein described in one of his critics as a “tectonic hallucination,”[16] the painter seated in an armchair devotes all his attention to the canvas in the middle of the room. While his palette rests in his left hand, his right hand, with the utmost concentration, is completing the contour of the profile. Behind the easel, a bust of a woman on a low table. Contrary to the spectator's expectations – and to the logic of the atelier – Picasso once again leads us astray. Who is the painter here, and who is the model? If we pay attention to the actual effects of the painter's work, the answer seems clear. He is drawing his own profile on the canvas. It is the figure of the artist, who paints and is painted at the same time. In the dialectic between seeing and being seen, the subject evolves from the agent of the action to its object in the grammatical sense. In this studio, the painter becomes one idea out of both figures.

Since the mirror is susceptible of providing the image of things that we see, it must also be capable of giving the image of entities that are ordinarily invisible.

– P. Mabille[17]

Blind reflections

During the 1930s Picasso works on paintings in which the entanglement in space eclipses the activity of the mirror that the artist confronted his model with. In La Muse of 1935, we attend a drawing session (fig. 4). One of the women, seated on a pillow, is drawing in her sketchbook, while the other is slumbering, resting her head on the table. The light barely penetrates the room, since the window is covered by a screen stretched along the entire length of the wall. The darkness of the scene is highlighted through deep shades of green and violet. In front of the women, the mirror does not reflect anything of the scene of drawing and melancholic reverie. Instead, it reveals a sort of disruption of perspective and a fantastic abstraction, evoking the bouquet of flowers on the table where the young woman is resting. Jeune fille dessinant dans un intérieur, from the same year, represents a parallel situation. A draughtswoman, a sleeping girl on a table, a window blinded with fabric and a mirror. In this scene, the glass takes on dark colours. The black, broken up by the blood-red, reveals a kind of entry into another world, as if the object had another side, which remains invisible to the women, one busy drawing, the other immersed in a profound dream. A final revision of the mirror scene in the 1930s, Femme accroupie, shows the female model in a fully lit, albeit claustrophobic, interior (fig. 5). The light coming through the half-open window becomes the motif for the reflective hyperactivity of the glass, in which geometric structures in black, red and pastel green appear. The woman doesn't notice this extraordinary activity. Turned away from the mirror, she looks at the sheet of paper on the floor in front of her. Has she just received a letter, or is she already thinking about the answer?

In a small painting, Nu couché from 1932, Picasso placed a mirror behind his model. The position of the object is strategic here. The eroticism of this tiny canvas culminates in its reflection. The spectator, who is already confronted with the woman's naked breasts and sex, has to respond to the next image, the one en abîme, revealing the young girl's buttocks. A similar exposure of the model appears in a painting from the same year, where Picasso, in the intimacy of an alcove, adds another perspective to his composition. Le Miroir unveils the image of a naked girl whose dream is interrupted by a sudden reflection of the back of her body emerging from the glass (fig. 6). In this spatial-corporeal constellation, the painter again operates from two perspectives, the latter of which is only possible through the use of the mirror. The insertion of the object introduces a new standpoint, foreign to the spectator, as if another pair of eyes were appearing in the relationship of gazes. The model in Picasso's painting, who has fallen into a deep sleep, is unaware of the double observation of her body. The reflection in the mirror turns the spectator into a voyeur who – willingly or not – participates in an erotic contemplation of the young girl.

Though objectifying the woman, Le Miroir reveals the transformative potential of her body’s reflection, even if it is reduced to her reproductive capabilities. The reflection in the glass exposes, in effect, the inverted female buttocks, so that the woman's sex could be potentially visible. From its depths springs a green stalk, in which Robert Rosenblum recognised the outline of a “fertilised seed.”[18] The reflection in the mirror – which the subject itself does not see – thus reveals the woman as a “goddess of fertility,”[19] an archetype of feminine representation which even the avant-garde could not escape from.[20]

A shadow of death

What does Picasso show us in another mirror? In a composition enlivened by a patterned wallpaper in red and yellow, almost entirely focused on the act of looking in the glass, Picasso allows his model, in Jeune fille devant un miroir of 1932, to confront her reflection for the first time (fig. 7). The young girl reacts to this privilege with avidity. She embraces the mirror in an ostentatious gesture involving her hands, which are stretched out to the extreme by the painter in order to reach the surface of the reflecting object. She has two bodies as well as two faces. Two aspects of the same body intersect in the act of a profound self-assumption. The young, powdery face-half corresponds to the exposed abdomen and breasts. The right side of the girl's face brightens the intense yellow that contrasts with the dull tones of her skin. Despite her involvement in the act of observing the surface of the mirror, the young girl does not find her physical reality in the reflection. She encounters a frightening figure with dark plum skin, who does not respond to her gaze, but stares emptyly into the room.

The moment experienced by the young girl in Picasso's painting is the moment when two worlds meet, the physical world that comes from corporeal experience and the metaphysical one, being its image. The double created in the mirror becomes a pretext for Pierre Mabille to diagnose an “externalization of the content of the unconscious.”[21] As the physician notes in his essay published in one of the issues of the revue Minotaure from 1938, “it externalizes my ‘self’,”[22] the other half of which is that captured on the other side, in the speculative space of the mirror reflection. The painter facilitates the young girl's divinatory experience by placing her in front of a particular object. The mirror which the model is confronted with is a psyche, a cheval glass known in France since the end of the 18th century.[23] In Greek, its name means soul. The young girl is therefore not so much looking at her reflection in the mirror as at her soul.[24] The mirror thus becomes a device for introspection into the model's inner world. Is it really so dark?

Looking at one's own reflection or, as we have just seen, looking into one's own soul means confronting the deepest recesses of oneself. Remembering the day Guillaume Apollinaire – an important figure for Picasso – died, Brassaï asked: “Would Picasso think of the appalled expression on his face on that sad day in November 1918? [...] At the Hotel Lutetia, he was about to shave...”[25] When news of his friend's decease reached him, Picasso could only conceive the idea of death in the image of his own reflection. “It was from then on,” said Brassaï, “that his hate of the mirror – all mirrors – began [...]. Having seen the shadow of death pass over his own face that day, he stopped drawing or painting himself...”[26] Death was now an inseparable element in the ambivalence of the mirror reflection.[27]

Whatever Picasso's relationship with the mirror and the mysteries of its reflection, the women in his portraits never had the opportunity to experience it. Turned away from the mirror, sleeping next to it, writing or reading beside it, their eyes never reach its formative reflection, the only one capable, according to Lacan, of enabling the subject to overcome the fantasies of a fragmented body. In a covered room, where no light comes in, far from the surface of a mirror that reflects nothing but mystery, Picasso's model remains in the fantasy of the incompleteness of her being. If, however, the model succeeds in perceiving her double in the mirror, the reflection becomes for the artist what the form represented for him in his Cubist period.[28] Picasso's fascination for the female body becomes a pretext for experimenting with the mirror, whose reflection offers him what John Golding described as a “physical totality.”[29] The reflecting glass enables Picasso to escape the trap of a multi-perspectivist image of reality. While his Cubist portraits focused on the visible of his model, the mirror allows him to discover her invisible. The possibility of confronting her with its reflection gives the painter the opportunity to oppose two aspects of the same person, in which fertility becomes the antithesis of death.

[1] Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Enzyklopädie der philosophischen Wissenschaften im Grundrisse, vol. 3, Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp, 1995, p. 87 (my translation).

[2] Brassaï, Conversations avec Picasso, Paris, Gallimard, 1964, p. 147 (my translation).

[3] Rosalind Krauss, “Notes on the Index: Part 1,” in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press, 1986, p. 203.

[4] The date of the two prints from the same negative is not certain, as Anne Baldassari warns us. See in particular Anne Baldassari, “Autoscopie,” in Picasso photographe, 1901-1916, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994, p. 85.

[5] It is impossible to identify accurately the drawing hanging on the wall of the painter’s studio in this shot. Anne Baldassari suggests that it could date from 1906 or 1907, when Picasso was occupied by a redefinition of the human figure for Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Ibid., pp. 82-85.

According to François Dareau, who cordially provided me with all necessary information about the sketchbooks held in the collections of the Musée national Picasso-Paris, the highly probable origin of this drawing could be Picasso’s trip to Gósol in 1906. In any case, the drawing may have been executed as a part of Picasso’s work in the sketchbooks dated between 1906 and 1907 (inventory numbers: MP1858, MP1859 and MP1861).

[6] Relying on a sketch of a male figure in pencil on an envelope from 1919, Anne Baldassari recognises in the profile projected onto the framed drawing, the painter himself. Ibid., p 82.

Émilie Bouvard expresses her doubts concerning the hypothesis that the shadow of the figure could be Picasso’s one and suggests that the photograph was taken in the context of an exhibition. See Émilie Bouvard, “L’Atelier,” in Picasso. Tableaux magiques, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Musée national Picasso-Paris, 2019, p. 105.

Whoever the owner of the mysterious shadow could be, the negative was part of Picasso’s personal collection and, as we shall see later, played a key role in the constitution of the painter’s figure in many of the canvases dedicated to the theme of atelier on which the artist worked between 1927 and 1929.

[7]Anne Baldassari, “Picasso ou l’insurrection de la peinture”, in Picasso surréaliste, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Flammarion, 2005, p. 174 (my translation).

[8] My title is inspired by Sigrid Schade, who stated in her essay that: “what makes the subject an individual is, paradoxically, that it is a dividual.” See Sigrid Schade, “Der Mythos des ‘Ganzen Körpers.’ Das Fragmentarische in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts als Rekonstruktion bürgerlicher Totalitätskonzepte” in Frauen, Bilder – Männer, Mythen. Kunsthistorische Beiträge, ed. Ilsebill Barta, Berlin, Reimer Verlag, 1987, p. 246 (my translation and italics).

[9]Jacques Lacan, “Le stade du miroir comme formateur de la fonction du Je telle qu’elle nous est révélée dans l’expérience psychanalytique,” Revue française de psychanalyse: organe officielle de la Société psychanalytique de Paris 4, October-December 1949, p. 450 (my translation).

[10] Ibid. (my translation).

[11] Ibid. (my translation).

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., p. 452 (my translation).

[14] In his excellent analysis of the painting, Victor Stoichita also recognises a mirror in the object in front of which the figure is engaged in the act of creation. His analysis differs from mine, however, in the sense that for the author the act of identification seems to have its origin in the work of art itself. In fact, Stoichita understands the figure in front of the mirror initially as one of the artist's works in the studio, a work that takes part in the construction of its creator's identity as a shadow. See Victor Stoichita, A Short History of the Shadow, London, Reaction Books, 1997, pp. 114-116.

[15] I refer here to a passage from Lacan's essay in which he understands the mirror stage as a “drama whose internal impulse precipitates from insufficiency to anticipation, – and which for the subject, caught up in the lure of spatial identification, engenders the fantasies that succeed one another from a fragmented image of the body to a form that we will call orthopaedic of its totality.” See Lacan, “Le stade du miroir,” op. cit., pp. 452-453 (my translation).

[16]Carl Einstein, “Pablo Picasso. Quelques tableaux de 1928,” Documents 1, April 1929, p. 35 (my translation).

[17] Pierre Mabille, “Miroirs,” Minotaure 11, May 1938, p. 18 (my translation).

[18] Robert Rosenblum, “Picasso and the Anatomy od Eroticism,” in Picasso in Perspective, ed. Gert Schiff, New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 1976, p. 84.

[19] Ibid.

[20] See Schade, “Der Mythos des ‘Ganzen Körpers’,” op. cit., pp. 250-251.

[21] Mabille, “Miroirs,” op. cit., p. 18 (my translation).

[22] Ibid., p. 15 (my translation).

[23] Carla Gottlieb, “Picasso’s ‘Girl before a Mirror’,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 24/4, Summer 1966, p. 510.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Brassaï, Conversations avec Picasso, Paris, Gallimard, 1964, p. 147 (my translation).

[26] Ibid. (my translation).

[27] Using the same passage from Brassaï’s memoirs, Anne Baldassari draws similar conclusions. See Baldassari, “Autoscopie,” op. cit., p. 81.

[28] John Golding, “Picasso and Surrealism,” in Picasso in Retrospect, ed. Roland Penrose and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, New York, Praeger Publishers, 1973, pp. 111-112.

[29]Ibid., p. 112.

Fig. 1

Pablo Picasso

Autoportrait à l'armoire à glace, rue La Boétie, Paris, 1921

Musée national Picasso-Paris

Don Succession Picasso, 1992

Fig. 2

Anonyme

L'Ombre d'un profil d'homme, Paris, s.d.

Musée national Picasso-Paris

Don Succession Picasso, 1992

Fig. 3

Pablo Picasso

L'Atelier, Paris, 1928-1929

Huile sur toile, 162 x 130 cm

Musée national Picaso-Paris

Dation Pablo Picasso, 1979

En dépôt au Centre Pompidou - MNAM-CCI, Paris

Fig. 4

Pablo Picasso

La Muse, 21 janvier 1935

Huile sur toile, 130 x 162 cm

Centre Pompidou - MNAM-CCI, Paris

Don de l'artiste, 1947

Fig. 5

Pablo Picasso

Femme au miroir (Femme accroupie), 1937

Huile sur toile, 130 x 195 cm

Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf

Fig. 6

Pablo Picasso

Le Miroir, 1932

Huile sur toile, 130 x 97 cm

Collection particulière

Fig. 7

Pablo Picasso,

Girl before a Mirror, Paris, March 14, 1932

Oil on canvas, 162.3 x 130.2 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York (NY), Etats-Unis

Gift of Mrs. Simon Guggenheim